India’s age-old pursuit of the ideal of becoming a responsible, reliable and self-dependent world power is manifested (personified) in PM Modi’s call for ‘Aatma Nirbhar Bharat’

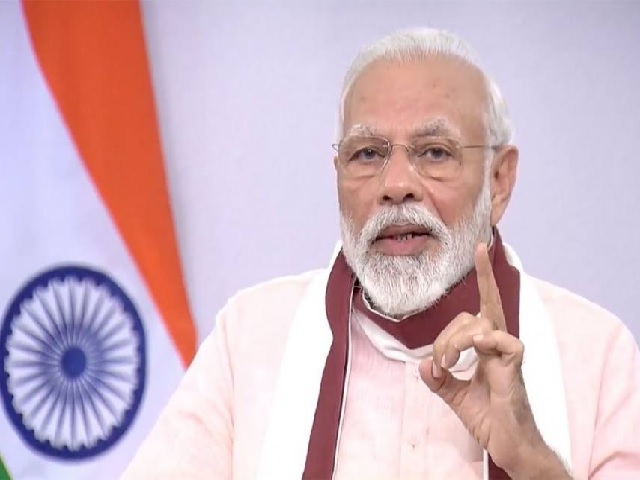

The quest for Aatma Nirbhar Bharat has been a long and arduous one. By referring to it in his historic address of May 12, 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has pointed at two aspects. One aspect that PM Modi indicated was that the quest for self-dependence will now have to acquire new dynamism and direction and that it is an aspiration which will have to find renewed expression in a world in which much of our established notions, structures, frameworks were suddenly hurled into a state of flux and remoulding. The other aspect that he referred was India’s civilisational world view, world-sense and world-approach. India’s civilisational aspiration has always been to rise and to be recognised as a resolute and yet benign power, whose focus, while being in the thick of trying to work out and elicit her strategic depth and scope, is also to work for global welfare, well-being and cohesion.

Such an approach, despite being ridiculed by many and often referred to as obsolete or esoteric, is and continues to be intrinsic to India’s world dealing. India’s rise is being seen as the rise of a determined but benign power, as a dependable and responsible power. Not only the acceptance of India’s call for instituting a World Yoga Day, which saw an overwhelming response and has now gone down in history as civilisational India’s moment of triumph, more recently, India taking charge of the Executive Board of the WHO, at such a crucial time in world history and India’s response globally to those countries in need of support to counter the pandemic, makes her come across as a mature power. Civilisationally India has spoken of enlightening the world — she has never looked at the world through the lens of subsidiarity. India is not led nor is she obsessed with the philosophy of considering everything under the heavens as belonging to her or made to be possessed or controlled by her.

For instance, India never had and will never have, the equivalent of the Chinese philosophy of ‘Tian Xia’ meaning ‘everything under the heavens’ belongs to the emperor. Journalist-academic Howard French, for instance, in his widely discussed work, ‘Everything under the heavens – how the past helps shape China’s push for Global Power’, discussing this dimension of how this drives China’s present dealings refers to Chinese political thinker, Yan Xuetong’s citation of an ancient Chinese classic — Book of Odes — which describes this mindset, ‘The term all under the heavens was virtually synonymous with the world. The title Son of Heaven referred to the person who ruled over all people on the earth as representative of Heaven.’ Chinese emperors, in ‘feudal times, called themselves Son of Heaven, which shows that they thought of themselves as rulers of the world.’ The driving idea, French argues, was that ‘under heaven’s canopy there is nowhere that is not the king’s land; up to the sea’ shores, there are none who are not the king’s servants’ and it illustrates the ambition for “world-leadership’ and domination.

India’s vision of ‘Viswa-Guru’ has a diametrically opposite, vision and aspiration. It was not about domination it was about dissemination and is driven by our intrinsic civilisational sense of being a positive agent of global change. A survey of some of the writings and utterances of some of our leading epoch makers, during the early days of our struggle for freedom, has this distinct leitmotif in them. It was that India needs to be free, to be able to be herself. She needed to be empowered so that she can contribute to the sum total of global welfare.

One of the leading voices of India’s cultural and local-industrial regeneration, philosopher Ananda Coomaraswamy, in his ‘Essays on National Idealism’, describes this aspiration. He is in a long line of epochal thinkers who have made the same point in their own ways. ‘The highest ideal of nationality is service; this service is impossible for us so long as we are politically and spiritually dominated by any Western civilisation.’ In his inaugural essay on the deeper meaning of the struggle for political freedom, Coomaraswamy, inspiringly and succinctly describes this, ideal when he writes, ‘for ourselves, the ideal is that of nationalism and internationalism. We feel that loyalty for us consists in loyalty to the idea of an Indian nation, politically, economically and intellectually free; that is, we believe in India for Indians; but if we do so, it is not merely because we want our own India for ourselves but because we believe that every nation has its own part to play in the long tale of human progress, and those nations which are not free to develop their own individuality and own character, are also unable to make the contribution to the sum of human culture which the world has a right to expect of them.’

The quest thus for a self-dependent India had also a larger global perspective. It was a yearning to be part of the world and to be a recognised and influential entity making a positive contribution to the sum of human culture. India’s quest for self-dependence, for being able to shape and direct its destiny — for political, economic and intellectual freedom — was not a turning upon oneself, her quest for self-reliance was not self-centred. She aspired to be self-reliant in order to be able to also contribute to the world as a free nation. PM Modi’s words renewed that aspiration and infused in it contemporaneity. He was referring to that ideal in his address of 12 May, when he said, that “India’s culture considers the world as one family, and progress in India is part of, and also contributes to, progress in the whole world.” He also referred to how “the world trusts that India has a lot to contribute towards the development of entire humanity.” India’s world view and approach, thus, is one which is, in the long run, sustainable. It is not exploitative, it is not hegemonistic.

The quest for self-reliance or self-dependence has to be ignited by the search for self-esteem. In his many writings, talks and public addresses Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, for instance, often spoke of the need to awaken the ‘spirit of self-reliance in the country” and for this, he argued that the rekindling of self-esteem was essential. Self-esteem is “essential for the development of the individual and the nation”, Deendayal Upadhyaya observed and it was necessary for every nation “to think about its centres or sources of inspiration, which must always be within” because if they are “alien, the situation becomes debilitating and destructive…”

The quest for Aatma Nirbhar Bharat is a quest for centres and sources of our inspirations. In the last six years since 2014, Prime Minister Modi has laid the foundations for the crystallisation of that quest. In the last year, he has imparted a new direction to it.

(The writer is the Director of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal)

Image Source: https://www.google.co.in/url?

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)