Commissioning of INS Vikrant by the Prime Minister is a restatement of India’s unchallenged maritime dominance and self-reliance across ages

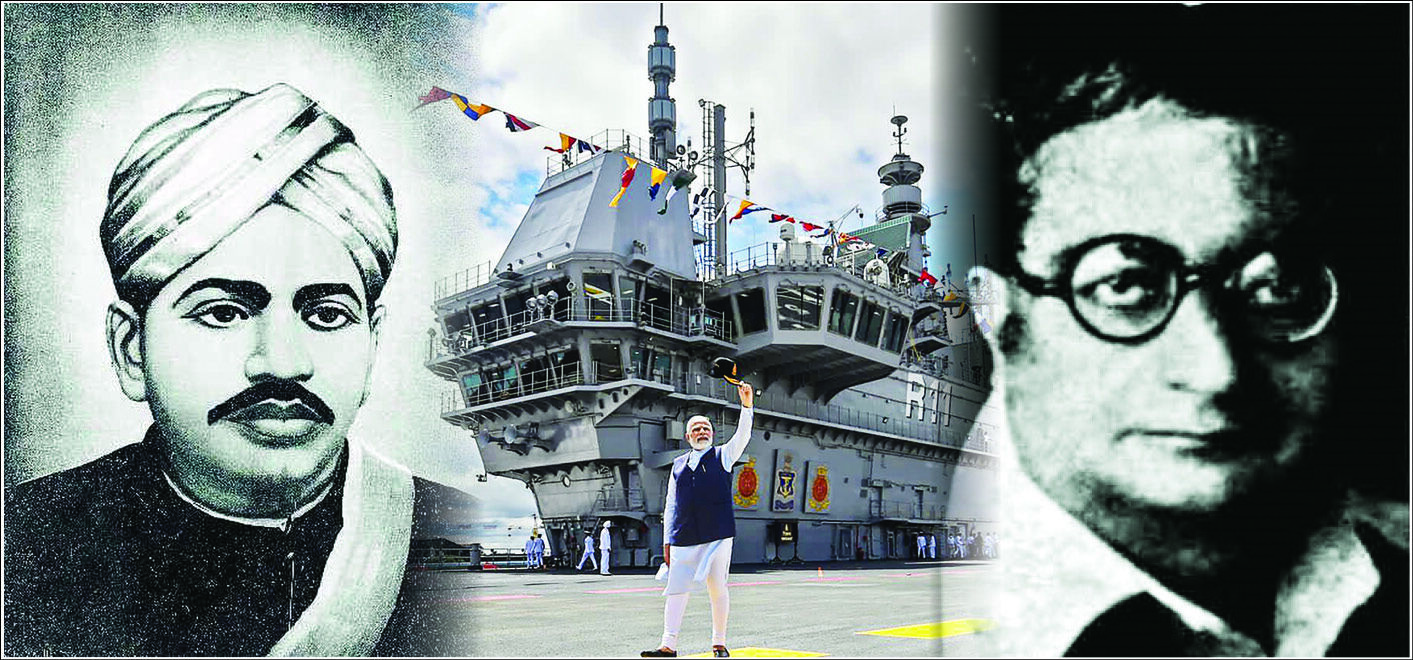

The historic commissioning of INS Vikrant by Prime Minister Narendra Modi is an epic tribute to the aspirations, struggles and hopes of those freedom fighters and revolutionaries who had envisioned a free and self-reliant India.

INS Vikrant, Prime Minister Modi said, “is a unique reflection of India becoming self-reliant.” One of the driving visions of India’s struggle for freedom was this intense urge of seeing India self-reliant. Independence without self-reliance, our thinkers argued, would be an incomplete independence. Prime Minister Modi also reminded us that both power and peace are complementary. India on the 75th year of her Swaraj, has internalised that axiom, that essential truth. In the last few years, she has effectively reflected that essence in her global dealings.

The new Naval Insignia which accords a permanent place of pride to Chhatrapati Shivaji’s emblem exudes a deeper symbolism when one realises that it reflects India’s intensifying urge for throwing off colonial symbols. A civilisational state rediscovers its civilisational symbols and in its march towards great power status and newness in modern times, puts to use those aeonic symbols. These rekindle aspirations of greatness and self-reliance. For a people long exploited, colonised and partitioned, the reinstatement of these symbols has a poignant and galvanising resonance. The new Insignia is reflective of both our continuing urge to reject and decimate layers of the colonial mindset and our continuing exertion for a comprehensive and all-round cultural self-recovery.

Civilisationally, Indians have had a long and insatiable urge and thirst for travel and peregrination. The urge to cross seas and mountains and of demonstrating our skills to connect, to coalesce and to exude knowledge, technology, high thought, arts, architecture and more, has been constant. It was such unceasing maritime movement that generated one of the greatest and most unique civilisational exchange, discovery and absorption across vast swathes of Asia. This civilisational infusion was led and dominated by civilisational India. The Indian Ocean used to be referred to as the “Chola Lake” and the Chola emperors’ flotillas dominated the Malacca Strait and East Sea up to Japan.

Lyrically describing this civilisational exchange through the medium of a rigorous and relentless travel, Raghuvira, formidable scholar of civilisation and the eighth president of Jana Sangh, wrote, “Indians were great travellers, adventurers, merchant men and artists…They went to the farthest corners of Asia. They had zeal and energy, a mission to help others which gave them strength to cross wide oceans, high mountains and waterless deserts. They went to the north, beyond the Himalayas into Tibet, China, Mongolia, Siberia. They crossed the deserts of Central Asia. They went beyond the seas to Africa in the West and Indonesia and Philippines in the East.”

While Indians undertook civilisational travel, the world too converged on India. Other civilisations and people looked upon India as the fountain of knowledge and of life-giving wisdom. In philosopher Philostratus’ work ‘Life of Apollonius of Tyanensis’, Stanford historian Grant Parker notes, “India emerges as a place of special knowledge, its religious specialists themselves the objects of pilgrimages…” In his classic ‘Asia and Western Dominance’, historian KM Panikkar speaks of how the “Indian Ocean, including the entire coast of Africa, had been explored centuries ago by Indian navigators. Indian ships frequented the East African ports and certainly knew Madagascar”. The Indian Ocean, since aeons, was a sphere of intense activity. Panikkar notes how, “Indian ships had from the beginning of history sailed across the Arabian Sea up to the Red Sea ports and maintained intimate cultural and commercial connections with Egypt, Israel and other countries of the Near East.” Long before Hippalus, the Greek navigator and merchant of the first century BCE, writes Pannikar, “disclosed the secret of the monsoon to the Romans, Indian navigators had made use of these winds and sailed to Bab-El-Mandeb. To the east, Indian mariners had gone as far as Borneo and flourishing Indian colonies had existed for over 1,200 years in Malaya, the islands of Indonesia, in Cambodia, Champa and other areas of the coast. Indian ships from Quilon made regular journeys to the South China coast. A long tradition of maritime life was part of the history of Peninsular India.” Yet these powerful navies were never used to subjugate, dominate or intimidate; “Indian rulers who maintained powerful navies like the Chola Emperors, or the Zamorins, used it only for the protection of the coast, for putting down piracy, and, in case of war, for carrying and escorting troops across the seas.” The Arthasastra, notes archaeologist and author KS Ramachandran, is the “only work known to us laying the rules and regulations of navigation.” The navigation department was “under the charge of a Navadhyaksa, the controller of shipping, with specific duties enjoined upon him. He had to obey the rules and restrictions imposed on him by the Pattanadhyaksa, an officer of the state comparable to the Commissioner of Ports of modern times.” Sangam literature, especially “Silappadikaram, Manimekalai, Pattinapalai, Maduraikkanji, Ahananuru, Purananuru are replete with references to the shipping activities of the Tamils.” The urge to regain India’s lost maritime dexterity and freedom of movement on the seas also propelled our freedom fighters. VOC Chidambaram Pillai’s success in countering British monopoly in navigation and his subsequent incarceration and ruination by the British remains one of the most inspiring episodes in the saga of our freedom struggle. Chidambaram’s “Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company” had, among its principal objectives, to train Indians, Ceylonese and Asians in ship “building techniques”, to “start institutions to teach the youngsters about the ship building industry” and “to instill unity amongst all races and classes of people belonging to the Asian continent through this means.” The objective was to break the colonial monopoly and to re-instill faith in Indians and in their ability to recover their lost maritime prowess and heritage. The brief success of the Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company, its championing of economic nationalism and swadeshi enterprise, earned for Chidambaram the sobriquet “Ship Floating Tamilian.” Repeated harassment of the company’s shareholders by a shaken colonial administration led to the eventual closure of the company. This collapse of the swadeshi maritime venture also led to the extreme political victimisation of Chidambaram who stoically withstood incarceration and torture. A seminal work that inspired Indian thinkers and intellectuals to further buttress the swadeshi narrative throughout the struggle for freedom was, interestingly, a voluminous work on Indian shipping. Avant-garde historian, and one of the leading minds of 20th century Bengal, Radhakumud Mookerji, himself one of the finest products of the national education movement that was led and ideated by Sri Aurobindo and Satish Chandra Mukherjee, in his then path-breaking work ‘Indian Shipping: A History of the Sea-Borne Trade and Maritime Activity of the Indians from the Earliest Times’ discussed at length the unique maritime capabilities of civilisational India. Mookerji argued, producing an elaborate plethora of evidence, on how India for “full thirty centuries stood out as the very heart of the Old World, and maintained her position as one of the foremost maritime countries” setting up “colonies in Pegu, in Cambodia, in Java, in Sumatra, in Borneo, and even in countries of the Farther East, as far as Japan.” India had succeeded in establishing trading settlements in “Southern China, in the Malayan peninsula, in Arabia, and in all the chief cities of Persia and all over the east coast of Africa.” To Mookerji, it was the early growth of India’s shipping, “and shipbuilding, coupled with the genius and energy of her merchants, the skill and daring of her seamen, the enterprise of her colonists, and the zeal of her missionaries, secured to India the command of the sea for ages, and helped her to attain and long maintain her proud position as the mistress of the Eastern seas.” His work went on to exert a deep influence on the evolution of the narrative of self-reliance and of self-recovery during those years of intense struggle. Prime Minister Modi’s inspiring address while dedicating INS Vikrant, encapsulated these past thoughts. It reflected and articulated that sacred aspiration, long-held and nurtured, of seeing India unbound, great and self-reliant.

(The writer is a member of National Executive Committee (NEC), BJP, and the Hony. Director of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal.)

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)