Rahul Gandhi lives up to his great-grandfather’s reputation—an ill-tempered, irritable, and intolerant guignol prone to indulging in bravado. His theatrics in Parliament evoke the same amusement today as Nehru’s did in the past

Replying to the Motion of Thanks to the President in the Lok Sabha, Prime Minister Modi regaled the House by recalling episodes from history, particularly those involving Nehru and his visit to the United States during the Kennedy administration.

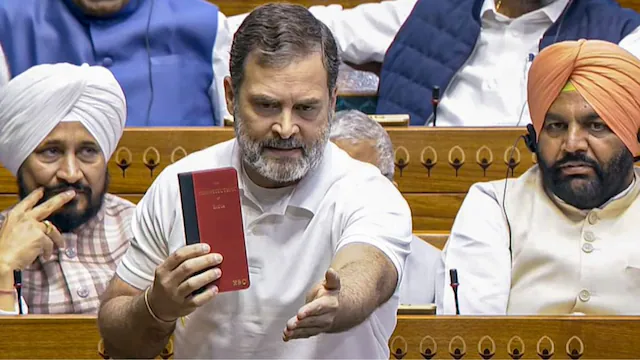

Listening to the Prime Minister mention the iconic RK Laxman’s cartoons, one wonders how Laxman, had he been present today, would have sketched and portrayed the first-ever Leader of the Opposition in a T-shirt, spewing inanities while trying to punch above his weight—both cerebral and corporeal. Seeing him capture the emotions of the pocket volcano that the LoP is would indeed have been a treat.

While putting together Jackie Kennedy’s itinerary for her visit to India in 1962, the US Ambassador to India, Kenneth Galbraith, assured an anxious JFK that Jackie could “count on a warm and agreeable welcome” and that “Nehru, who is deeply in love and has a picture of himself strolling with JBK [Jackie] displayed all by itself in the main entrance hall of his house, is entirely agreeable.” Jackie must have reminded Nehru of Edwina Mountbatten, who had died in 1960.

In his book JFK’s Forgotten Crisis, referred to by Prime Minister Modi in the Lok Sabha, Bruce Riedel also tells us that the US embassy in India “had rented a villa for Mrs Kennedy to stay in, but Nehru insisted after she arrived that she stay in a guest suite at the prime minister’s residence. It was the suite often used by Edwina Mountbatten.”

Rahul Gandhi churlishly resorted to a canard on the floor of the House, claiming that Prime Minister Modi had asked for an invitation to Trump’s inauguration. He has not been able to substantiate his statement, and it is only right that a privilege motion be initiated against him for uttering a blatant mensonge that would have made even Goebbels cringe! What is substantiated, however, is Nehru’s grovelling request to JFK to rescue him from the Chinese.

On 28 October 1962, JFK wrote to Nehru “assuring him that the United States fully backed India against the Chinese attack” and promised “both moral and tangible support if India sought help.” With all his past bravado evaporating, Nehru asked for US support. Riedel writes: “Asking for American arms was a humiliating moment for the prime minister, who had prided himself on Indian independence and neutrality. He knew he needed JFK’s help, but did not want to be seen to be abandoning his principles…” That pride and flourish obviously stood on a scaffolding of false notions and delusions.

In an incisive character portrait of Nehru, Nehru: The Lotus-Eater from Kashmir, veteran journalist and repository of the Nehru years, DF Karaka, writes of Nehru’s repeated refusal to take the “active advice of seasoned experts on their subjects.” It is known, for instance, that he repeatedly ignored Hugh Richardson’s warnings about Chinese designs on Tibet. An irritated Nehru eventually asked Richardson, a recognised authority on Tibet, to pack up. “It is now an open secret,” writes Karaka, that “the Chinese invasion of Tibet came as a complete surprise to the Indian government.” Neither Sardar Panikkar, India’s scholar-ambassador to Beijing, nor the new Indian representative to Lhasa, Dr Sinha, had any intelligence on Chinese troop movements.

When he heard of the invasion, a furious Nehru cabled Panikkar: “Either you did not explain our point of view to the Chinese, or you did not understand what the Chinese told you.” Two days later, writes Karaka, a “cool and collected ambassador replied that he knew nothing of the invasion until he heard of it over All India Radio.”

A typical Nehruvian bravado was articulated when he declared, “Let us make up our minds to live on food we produce or die in the attempt.” He did not call upon the people and experts to focus their energies on achieving self-reliance in food production. Many states witnessed starvation deaths as a result of this misplaced idealism. In the end, as Karaka laments, “far from stopping our imports of food, we found ourselves in the humiliating situation of not being able to afford to pay for the food we imported. We had to request credits from the United States and other nations who came to our assistance.”

The Chief Minister of Madras convinced Nehru to visit Rayalaseema, then reeling under a severe bout of starvation. “Nehru could spare but little time for the starved; he rushed through the district with an impatient look of annoyance on his face. He was annoyed with the whole state of affairs, annoyed with the crops that failed, he was annoyed with the people because they were starving. He told them not to look at his government so helplessly,” writes Karaka, who had followed Nehru on that visit and covered it.

One more instance of his ‘historic’ bravado led to complicating the Kashmir situation for a seemingly interminable period. Rushing to Kashmir after the first wave of the Pakistani raider attack had been repulsed by the Indian Army, Nehru got carried away and publicly declared—without taking anyone into confidence, neither the army, nor his government, nor other leaders—that “when the process of liberation was over,” the Kashmiris “would be free to choose whatever form of government they desired.”

The dégringolade that followed was swift. The sequence of events in Kashmir is too well known to bear repetition. Such bravado repeatedly emanated from Nehru, who always believed that ruling India was his family’s destiny. His heirs continue to cling to that false belief. The abominable reference to the President of India made by Sonia Gandhi and endorsed by Rahul and Priyanka Gandhi stems from that same fundamentally fascist and entitled mindset.

Contrary to what Congress ideologues would have us believe, freedom was repeatedly bludgeoned under Nehru. Karaka writes of how Nehru presided over the “slow destruction of the normal processes of democracy.” Having himself been at the receiving end of the Nehruvian apparatus’s wrath, Karaka’s case was becoming the norm under Nehru.

“As one who has tasted official wrath on more than one occasion,” he lamented, “I know what it feels like to be a ‘free’ man in Nehru’s India. Time and again, I have been dragged through the law courts on charges which the government has not been able to prove or substantiate. Acquittal follows in due course, but in the meantime, one is made to suffer the costs of the long process, for which acquittal in the criminal courts brings no relief.”

For Nehru’s government, the best way to silence its critics, Karaka pointed out, was to “declare a nerve-war on them.” On a seasoned critic like Karaka, it had perhaps little effect, but “for the meek,” it was “nerve-shattering.” There was “no respect for the liberty of an individual, and even less for his self-respect.”

Lathi charges and police firing were common occurrences in Nehru’s India. Students and farmers were fired upon; anyone protesting was bludgeoned with lathis. India under Nehru, Karaka caustically observed, “is gradually becoming a police state; civil liberty was dead in more senses than one.” It was “not only shot down by authority in the literal sense of the word,” but it was also “bound down in heavy chains, as even a cursory glance at our police records will indicate,” Karaka recorded.

Nehru, he argued, “could not be unaware of all this,” yet he maintained a “sphinx-like silence.” The Nehru “who once sat in a bullock-cart behind Gandhi, humbly joining his hands to greet his people, now allows his minions to ride in a slow but sure moving steam-roller, crushing down every head that bobs up against the administration.”

By 1953, six years into power, Nehru was becoming increasingly intolerant, irritable, and prone to public eruptions. “The list of people with whom Nehru is angry is growing daily. The more ground he loses, the more despotic he becomes, as those who have dealt with him over a long period of years say.” In fact, even Nehru’s acolytes, servitors, and faithful adherents voiced concern over his “growing intolerance,” Karaka noted. “They feel that he will break down one day in a sorry spectacle of shattered nerves and frayed temper because of his inability to accept the fact that people have a right to differ from him.”

By this time, the crowds that followed Nehru, observed Karaka, went to him in “a questioning sort of way,” while others “went out of amusement,” just as people “go to hear pretentious tub-thumpers in Hyde Park, only to listen to the amusing nonsense they speak.”

Rahul Gandhi’s intervention in the Lok Sabha brought back memories of Karaka’s perceptive tract. Rahul lives up to his great-grandfather’s reputation—an ill-tempered, irritable, and intolerant guignol prone to indulging in bravado. His theatrics in Parliament evoke the same amusement today as Nehru’s did in the past. Most of those who heard the pretentious tub-thumper in the Lok Sabha that day, including members of his own party, found his nonsense amusing. After all, the dilettante “Lotus Eater from Janpath” has repeatedly proved to be an adroit entertainer!

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)