Refreshing view from prism of Indian ethos

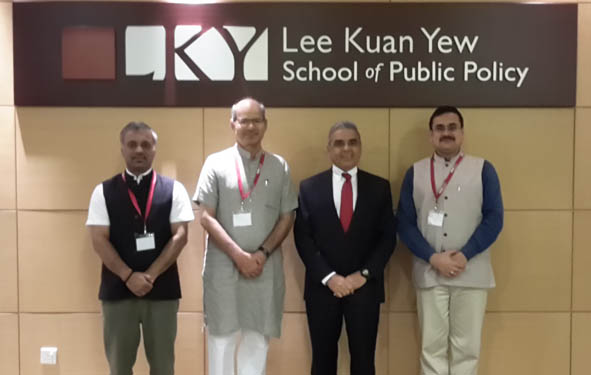

A batch of students at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore, prepared a detailed report on ‘Governance and Policy for Ganga Rejuvenation’. It was a laudable effort

When a number of ‘Ivy League’ universities in the West and their academic cartels are busy dissecting and theorising an imagined degeneration of India under the Narendra Modi regime, when a number of migratory intellectuals, who have spent an entire lifetime in the West debunking civilisational India and have made a fortune by raising a false spectre of fascism looming over India under a ‘Hindutva’ regime, when a number of institutes based in the West that study India, are all working hard at generating a dishonest discourse of India’s democratic experiment, it was refreshing to see a particular university and institution work on generating a positive discourse around a flagship scheme launched by the Modi Government over the last one year.

The Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore, in an interesting effort, saw its Master of Public Administration batch of 2014-15 prepare a detailed report, ‘Governance and Policy for Ganga Rejuvenation’, under its Governance Study Project. Consisting of 13 meticulously researched chapters, the attempt was to expose those who have undertaken the course, mainly from across Southeast Asia, including India, to understand the challenges, intricacies and innovativeness of the entire project of cleaning India’s sacred, sustaining and life-giving Ganga. The participants in the project were clearly enthused with the effort, and one could see the deep sense of involvement they had already developed with the river, with India’s civilisational view of it and with the herculean effort now being made to cleanse it of impurities. It was interesting to see how a few students, from a Southeast Asian country that had a deep civilisational connect with India, referred to Ganga as “our sacred river”.

The report took a comprehensive and historic look at efforts to clean Ganga over the years. Sections, such as ‘Historical Evaluation of Ganga Action Plans: Lessons learnt’, ‘Managing Competing Demand for Water in the Ganga: Lessons from the Yellow River’, ‘Principles of Waterfront Development — lessons from Varanasi’, which also saw a discussion of how the Sabarmati River front was transformed, ‘Educating the Youth: Facilitating a sustainable transformation of Ganga’ — which took into account the important role that education in environment can play in nurturing youth who would grow up to be future decision-makers, made the exchange rich and very interesting.

Generally, reports overlook the crucial dimension of education and simply limit the discussion to evaluating official frameworks and technical aspects. This report, however, brought in a new dimension through the education section which essentially examined how “education can be a key driver of change in the attitudes and behaviour of youth in Varanasi, fostering heightened awareness and greater environmental protection of the Ganga”. After discussing each chapter, students came up with recommendations and suggestions. There was clearly a deep appreciation, among them, of the way Prime Minister Modi had envisioned the renewed effort of cleaning Ganga.

Such occasions are also an opportunity to make interventions and put forward and discuss the great changes that have begun taking place in India over the last one year.

One discussed how Mr Modi had taken head-on the task of addressing India’s social challenges — such as sanitation, protecting the girl-child, building toilets, cleaning rivers etc, and had himself set the process in motion by wielding the broom to clean streets and the pick axe to de-silt Ganga. The forum provided an opportunity to flag the fact that the Prime Minister invited direct suggestions from citizens on every aspect of governance through interesting initiatives that connect with citizens, thus helping evolve a more participatory approach to governance. It also provided an opportunity to discuss the new efforts being made in education in India and how environmental education in India could be shaped and could derive from our vast civilisational knowledge of balanced living. Civilisationally, Indians have always looked upon nature as living entities and identified them with the embodiment of motherhood.

The session on regional collaboration in the Ganga basin gave one an opportunity to discuss how the vision of Saarc has graduated in the last one year to that of a “shared zone of prosperity” with Prime Minister Modi recalibrating India’s approach to her neighbourhood. The historic success of the land boundary agreement and the Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal network as an epochal achievement in the region that would re-define frameworks of engagement, could also be discussed in some detail. Quoting Mr Modi that “rivers must unite and not divide”, one pointed out how he had frankly discussed the Teesta issue and committed to solving it. The researchers were asked to take into account this changed neighbourhood scenario.

It was an opportunity to point out that since India and Bangladesh shared around 54 rivers and India had a varied federal structure, it made the addressing of the Teesta river issue more complex, while also offering scope for a comprehensive and wide settlement of the matter. One observed that in this evaluation of the regional collaboration one had to take into account Mr Modi’s effort at redefining the approach to India’s federal structure and of how he has “federalised foreign policy” in the last one year by encouraging States to take part in external outreach.

Discussing the section on harnessing international aid for Ganga rejuvenation, the LKY School report, interestingly, made crucial observations when it argued that international aid agencies cannot act as interveners in India but must act in support of the Government of India’s development goal and must be, more importantly, politically neutral. This gave rise to the opportunity of discussing the issue of international aid agencies and of how some of them have generated stress and conflict in Indian society by refusing to remain neutral. One argued that every sovereign nation reserves the democratic right to prevent any external intervention in any form and manner and, therefore, when India sets up a multi-layered checks and balance system or calls for a modicum of accountability from international aid agencies and asks them to adhere to the legal and financial system of the land, it essentially acts within its right of preserving its sovereignty and integrity. The Indian High Commissioner to Singapore, present on the occasion, saw this as one of the key points made.

It was an exercise that stood apart from the clichéd habit of hosting fear-generating discussions on how India was in the grip of an oppressive ‘corporate-communal alliance’. But then, those who have raised in conflict or peddled a conflict-generating ideology all their life, can hardly recognise the good happening in the India of today.

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)