Even after brutal suppression of satyagrahis in Goa, Nehru remained conspicuously silent, clinging to his ‘principles’ that would later be questioned by Jana Sangh

In the middle of 1946, Mahatma Gandhi wrote to the Portuguese Governor General of Goa that ‘in free India Goa could not be allowed to exist as a separate entity in opposition to the laws of the free-state.’ In June 1946, Ram Manohar Lohia had offered Satyagraha in solidarity with the Goan freedom fighters. Lohia was incarcerated and it sent ripples across the country. The Goan National Congress was formed in 1928 by Tristao Braganza Cunha and in 1946 it launched a campaign to liberate Goa which the Portuguese colonisers suppressed ruthlessly. Cunha was imprisoned, 1,500 Goans were also arrested and tortured. In expressing his solidarity with the movement, Lohia entered Goa and courted arrested.

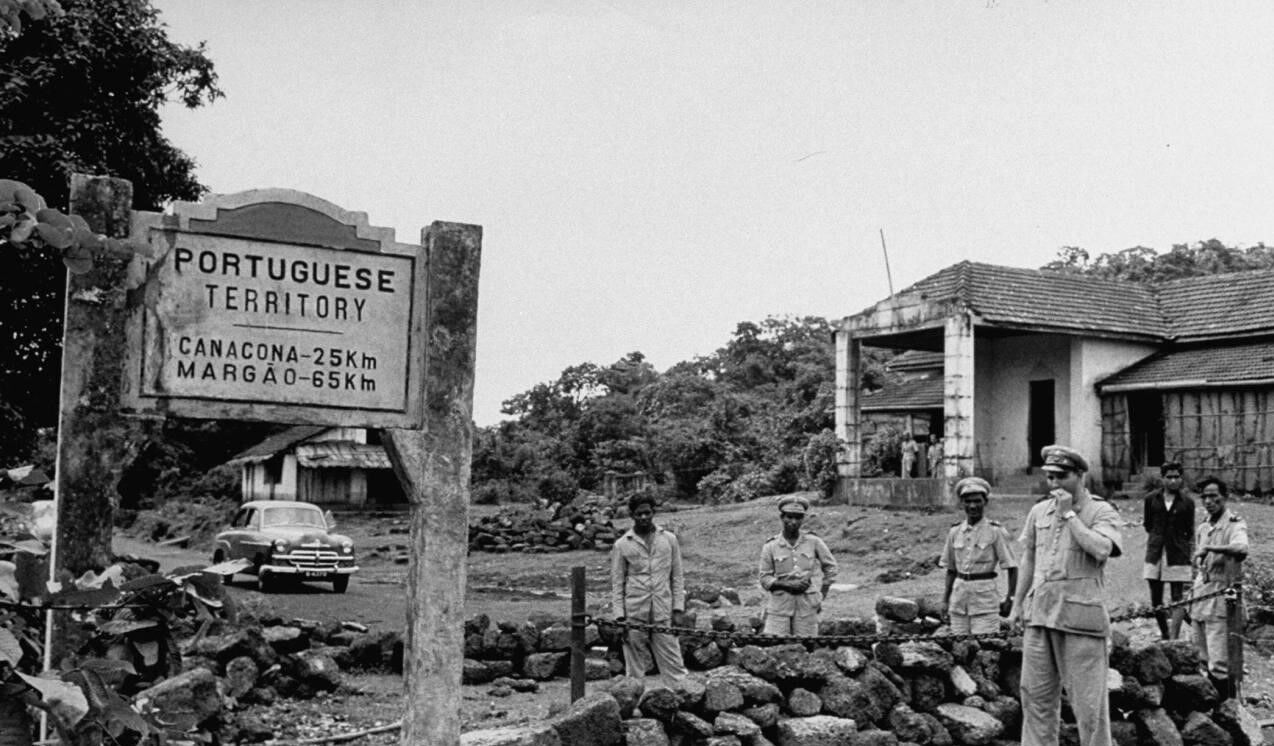

Post-independence, Congress under Nehru displayed an astonishing ambivalence on the Goan question. In fact, Nehru’s Goan policy aptly reflected his essentially procrastinating nature and his obsession with his international image. A Portuguese census of 1950 revealed that only 800 Europeans were living in Goa ‘who were transient Portuguese administrators and 316 people of mixed origin,’ the rest 6,50,000 were officially described as Indians. Yet Nehru did not think it prudent to exercise force to liberate this majority of Indians living under Portuguese occupation.

Sometime in 1954, The Guardian had also noted that it was ‘impossible that a pocket of Portuguese territory should exist in the midst of India, bred in the spirit of nationalism.’ While Portugal’s totalitarian Prime Minister Antonio Salazar breathed fire and ordered firing and torture of Indian Satyagrahis, Nehru continued sticking to his ambivalence. Salazar had once famously declared ‘The truth is that I am profoundly anti parliamentarian. I hate the speeches, the verbosity, the flowery, meaningless interpolations, the way we waste passion, not around any great idea, but just around futilities, nothingness from the point of view of the national good.’

When Salazar declared his imperial ambitions by saying that he would keep the Portuguese possession in India as ‘memorial of the Portuguese discoveries and a small hearth of the Western spirit in the East’, Nehru stuck to his pontificating. ‘The policy we have so far pursued has been,’ Nehru said, ‘(i) that we may not abandon or permit any derogation of our identification with the cause of our compatriots under Portuguese rule, (ii) equally we may not adopt, advocate or deliberately bring about a situation of violence…It is not the intention of the Government of India to be provoked into thinking and acting in military terms.’

In 1948, when Portugal ‘actively helped in gun-running to Hyderabad menacing the security of the country,’ writes Amiya and BG Rao, one of the finest chronicler-duos of Nehru’s tenure, ‘Nehru would take no action.’ As Acharya JB Kripalani lamented, ‘We should have given the Portuguese authorities notice to quit these pockets which they have occupied for centuries, as soon as the British had left. We could at least have taken action when they were gun-running to Hyderabad. To drive them away, as our military experts held, would have taken not more than a week or so. But we waited for years to drive them away, causing our people great hardship and suffering.’ When the Indian military operation did take place, the Portuguese, having ruled for 450 years, collapsed in 26 hours. But Nehru had waited for 14 years for effectuating these 26 hours!

On August 15, 1955, when Satyagrahis crossed over into Goa, and the Portuguese police fired on them killing no less than 20 and injuring a large number, protests spread to a number of other cities. These protestors were also fired upon. Even after this, Nehru’s stand continued to be confused and based on principles that had no application or relevance to the increasingly oppressive situation in Goa. Nehru reiterated that his ‘Government cannot conceive of patronising Satyagraha. If we want a settlement of this question by peaceful methods, we should not do anything which, though peaceful in itself, leads to violent methods.’

According to Nehru, thus, peaceful Satyagrahis were to be blamed for provoking firing on them. To those who demanded that military action would alone lead to integration, Nehru articulated his ‘principles’, ‘There is nothing we can argue with any person who thinks that the methods employed in regard to Goa must be other than peaceful, because we rule out non-peaceful methods completely…Once we accept the position that we can use the army for the solution of our problems, we cannot deny the same right to other countries. It is a question of principle.’

It did not matter to Nehru that his principles were delaying India’s integration. Homer A Jack (1916-1993) — an American clergyman, pacifist, founder of the Congress for Racial Equality and an author who had also written books on Gandhi — was present in Goa on the day Portuguese killed unarmed and peaceful Satyagrahis. Jack was astounded by the crime and also by the silence of the US. In a letter to the New York Times, he wrote, ‘Some of us who were inside Goa on August 15, when twenty unarmed Indians were killed by Portuguese soldiers in cold blood, and many hundreds wounded, wondered at that time why our American Government remained silent. And we were and have remained embarrassed by this silence.’

In its meet in Kolkata on August 28, 1955, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh condemned the ‘inhuman slaughter of unarmed satyagrahis on August 15’ and argued that it had ‘given rise to so much public anger’ which made it amply clear that ‘on this national issue the whole country is united.’ The Jana Sangh meet pointed out how, even after the slaughter of 15 August, ‘thousands of Indians have volunteered to participate in the Satyagraha.’ It proved that the ‘people of India’ were ‘now determined to continue the liberation struggle for Goa.’ The Jana Sangh attacked the Congress for always loudly talking about the ‘nobility and utility of non-violent satyagraha’ but failing to ‘make its own contribution in this struggle.’ The Congress, it advised, ‘instead of preaching the utility of peaceful means should have cooperated with other parties on this national question.’

The Jana Sangh had always stressed that the Goa problem could not be ‘solved merely by satyagraha.’ The events of 15 August, it argued, had made it clear that the ‘Portuguese administration would not be amenable to moral pressure only.’ It vindicated its stand that the ‘problem should be solved on the official level, including a police-action.’ It called upon the Nehru government to ‘determine a time-limit in which the Portuguese colonies [were] to be liberated by peaceful means or otherwise.’

The Jana Sangh had repeatedly and consistently called out Nehru’s ambivalence. It carried a sustained movement across the country on the need to liberate Goa and on the need to support the Goan liberation movement. As early as August 1954, Jana Sangh spoke of the continuance of foreign pockets in India after the withdrawal of the British as having ‘created a situation which is both a threat and challenge to the security and sovereignty of free India.’ It spoke of how the ‘inaction displayed by the Government of India regarding colonial outposts of Western imperialism’ had ‘encouraged Portugal to adopt a challenging attitude towards India and start a campaign of repression against the people who have been agitating for the merger of these territories with their motherland-India.’

To be continued…

(The writer is a member of National Executive Committee (NEC), BJP, and the Hony. Director of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal)

This article was published in Millenium Post on 16th February 2022

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)