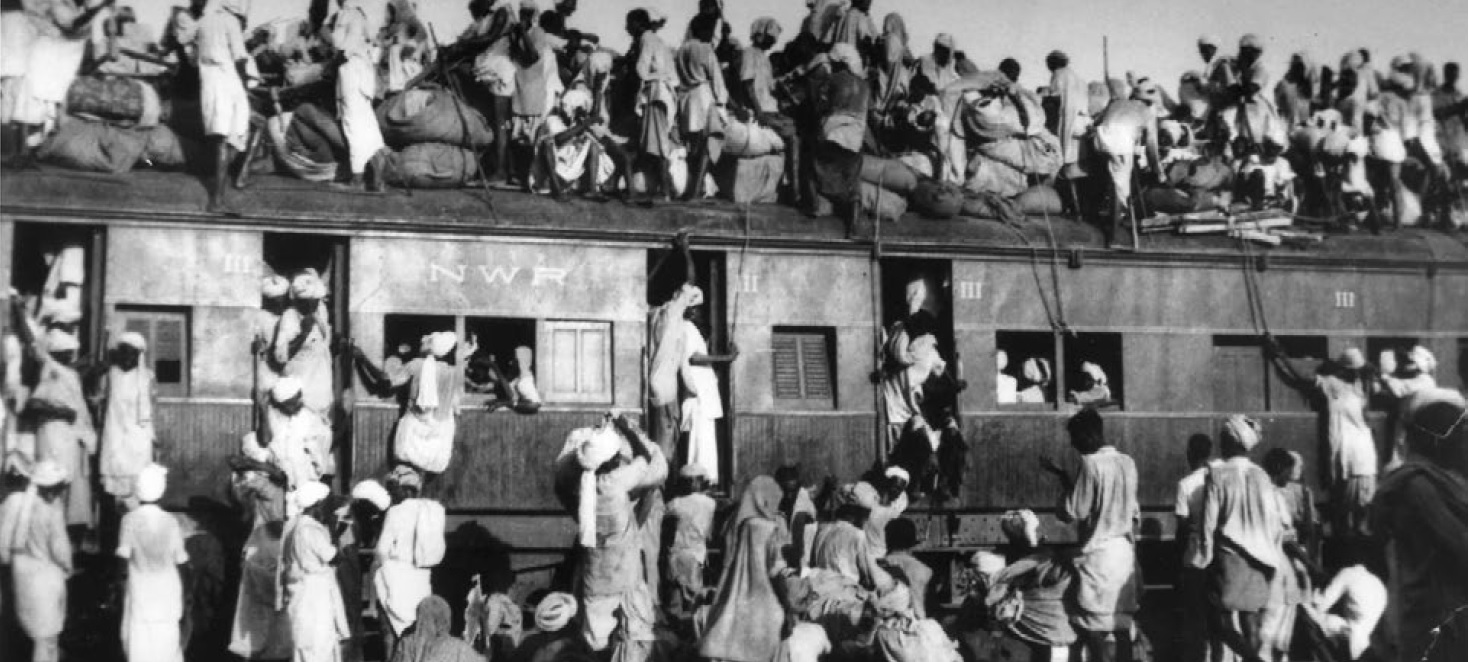

The historic and deeply symbolic decision taken by Prime Minister Modi of observing every 14th August as the “Partition Horrors Remembrance Day” in memory of the victims of partition is also an opportune moment to make efforts to systematically look at partition, the effects of partition and the horrors of partition. In his Independence Day address launching the seventy fifth anniversary of India’s Independence, Prime Minister Modi pointed at its deeper significance when he said, “While we celebrate our freedom today, we cannot forget the pain of partition that still pierces through the heart of all Indians. This has been one of the biggest tragedies of the last century. After attaining freedom, these people were forgotten too soon…We will henceforth commemorate August 14 as “Partition Horrors Remembrance Day” in the memory of all the victims of partition. Those who were subjected to inhuman circumstances, suffered torturous treatment, they could not even receive a dignified cremation. They must all remain alive and never get erased from our memories. The decision of celebrating “Partition Horrors Remembrance Day” on the 75th Independence Day is a befitting tribute from every Indian to them.”

Many aspects and dimensions of partition were allowed to melt away and to be gradually rendered opaque in our collective memory. Political parties like the Communist parties, who were at the forefront in supporting the Pakistan resolution, in supporting the formation of Pakistan and in arguing that Bengal must remain undivided and be included in Pakistan, produced legions of scholars and intellectuals who spent their careers whitewashing the actual partition narratives. As the late scholar administrator Nitish Sengupta, wrote in his opus, ‘Bengal Divided – 1907-1971’, ‘The Communist Party of India raised its voice against the partition of Bengal, although it supported the proposal of Pakistan with Bengal as a part of the new State.’ By clever manoeuvring couched in dialectical jargons Indian Communists well concealed their role in incubating Pakistan.

The role of the Indian communists in fomenting Pakistan, in siding with the Muslim League, in supporting ‘Direct Action’ and in suppressing the horrors of partition narrative has been huge and yet it is intriguing as to how this dimension of their treacherous behaviour has hardly ever dominated our discourses on partition and Pakistan. To Rammanohar Lohia, for instance, the fact that this treachery did not leave a lasting negative impression on people was in itself intriguing, as he observed, ‘I am somewhat intrigued by this aspect of communist treachery, that it leaves no lasting bad taste in the mouth of the people.’

The partition on the Eastern front and its effects lingered for long. This continued partition, as some have referred to it, has not been adequately discussed. The fact that from early 1950 continuous waves of refugees started coming into West Bengal having been pushed out and uprooted overnight, the fact that these waves kept coming – refugees, victims of genocide and pogrom – because Pakistan had declared itself as an Islamic state, is a saga, which has not been studied or adequately highlighted but which nevertheless gives a comprehensive insight into horrors of partition long after it was brought about.

In the context of the declaration of August 14 as ‘Partition Horrors Remembrance Day’, it is relevant to recall a most poignant narration of an episode that Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee made in Parliament on 7th August 1950, when the House discussed the Bengal situation. Dr Mookerjee referred to a veteran Congress leader from East Bengal, whom Prime Minister Nehru too knew well, a man who, as he put it, was not afraid of his life, who was not a coward and who was still in East Bengal. “He came to see me about three weeks ago,” Dr Mookerjee told the House, “And his words are still haunting me. He had seen West Bengal and moved about the place. He has seen the terrible misery of millions of refugees who have come to West Bengal. He told me: “Dr Mookerjee, I have seen West Bengal. In East Bengal there are thousands of Namasudras who are waiting to come over. If I come away, they will also come away, whatever happens to them. That is why I am sticking on there, though I know it is impossible for them to stay. I see nothing but death on either side, death in East Bengal and death in West Bengal but with this difference. In West Bengal it is death without dishonour whereas in East Bengal it is death with dishonour.” This one description, in a sense, epitomises the death-dilemma of those who were uprooted because of partition. The partition horrors narrative must bring these aspects, these forgotten personalities who withstood the all-consuming onslaught of deracination, to the fore and accord them permanent space in our collective discourse on partition.

Kisan Mazdoor Praja Party (KMPP) Member of Parliament from New Delhi, Sucheta Kripalani’s description of the refugees in Kolkata, was equally enervating, when she told Parliament, in March 1953, during the discussion on grant for refugees, that the Nehru dispensation was failing to handle the issue in the human way.

At the forefront of refugee relief herself, Sucheta Kripalani had closely worked on the ground since the time of partition, ‘Take the standing scandal of Calcutta’, Kripalani told the House, ‘What do you see. You see stations. The moment you reach Calcutta, what do you see? You see people are living on the platform for days and months and they are trying to gain their livelihood by selling some pakodis and by such other means. They were respectable citizens, cultivators or peasants or small shopkeepers. What have they become? They have become beggars and criminals: their women are becoming prostitutes…Our Prime Minister says a lot about the ‘human touch’. I want to see that ‘human touch’ in solving the lot of these miserable refugees.’

These victims of eastern partition have mostly been forgotten, and the literature that has been churned out in Bengali and in other languages have mostly focused on life after partition in West Bengal and not so much the causes of forced migration, persecution and eviction. Like Holocaust deniers in the West and across the world, a section has also denied the eviction of large sections of Bengali Hindus from Eastern Bengal post partition; this sector has not produced the kind of prolific artistic and literary output that could have been done. It served a certain ideological line to keep this narrative under wraps or in the margins. The horrors of partition were never really discussed except in a few books and by a few authors and that too primarily focused on life after partition and did not deal with the how and why of being uprooted.

In the introduction to his unfinished, ‘The Prolonged Partition and Its Pogroms’, late A.J.Kamra, has argued that books such has his, ought to encourage ‘others to write down and publish their experiences with the Partition’ and that ‘the genocide in East Bengal deserves as much attention as the Holocaust of the Jews.’

The ‘Partition Horrors Remembrance Day’ offers a renewed scope to discuss, argue, record, publish and disseminate the many dimensions of partitions hitherto suppressed and marginalised.

(The writer is the Director of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal)

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)