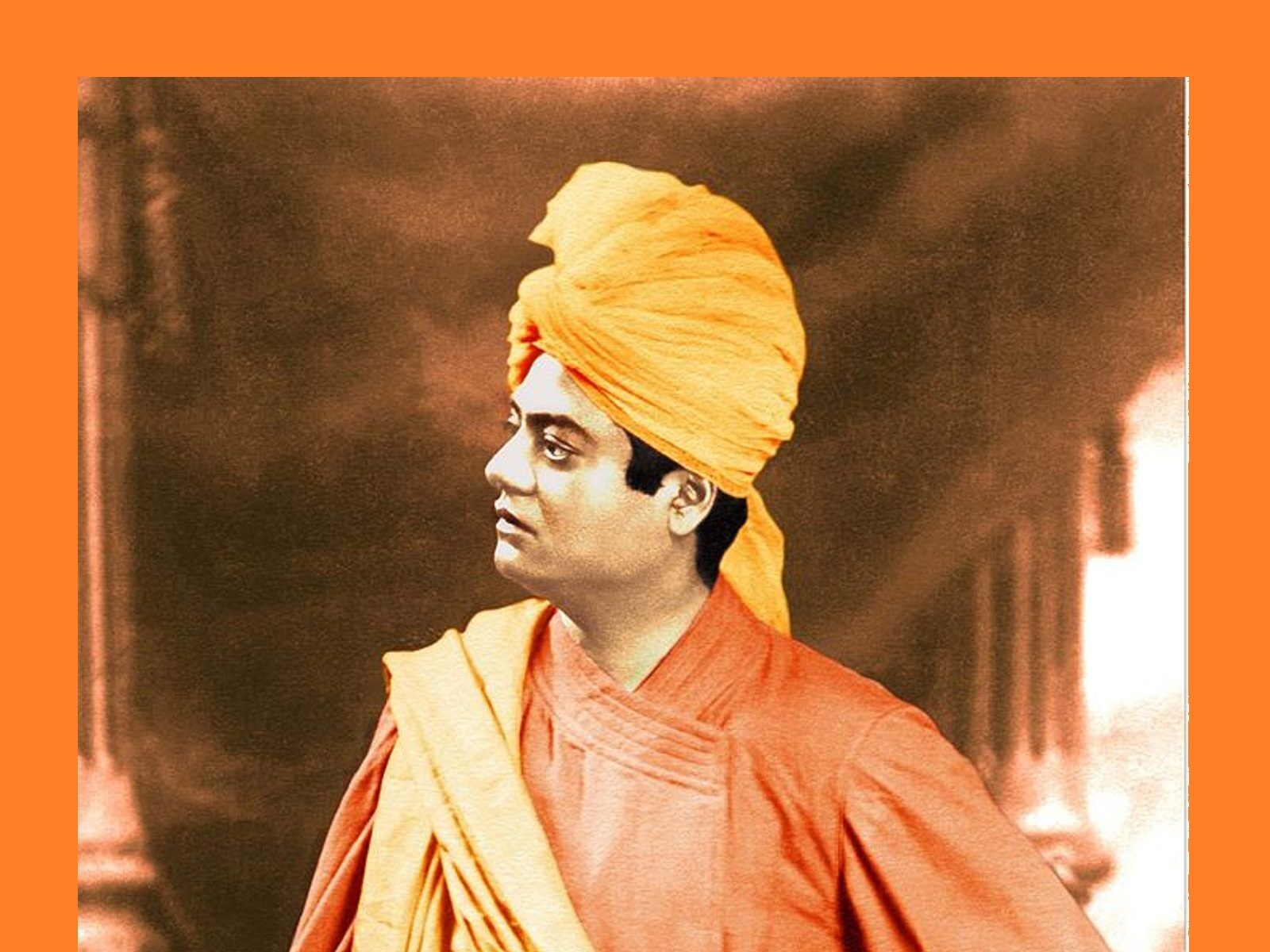

As one of the pioneers of nationalist movement, Vivekananda set the stage for India’s freedom half a century before it actually materialised

Swami Vivekananda’s message at the World Parliament of Religion made Indians realise their capacities and sowed in them the yearning for freedom. A leading socio-political historian of his era, Biman Behari Majumdar writes that Swami’s “triumphant return from his first Western tour in 1897 opened a new era in the history of nationalism in India. India had never before heard such a message of neo-Vedantism, strength and fearlessness and, above all, such a clarion call to abjure all the deities except the Motherland for the next fifty years.”

Laying the foundation that would crystallise Indian nationalism, the Swami gave a call at Madras on 14th February 1897 to worship the motherland alone and exclusively for the next fifty years: “…give up being a slave. For the next 50 years this alone shall be our keynote — this, our great Mother India. Let all other vain gods disappear for the time from our minds.” Nothing illustrates better the fruition of the Swami’s ‘prophetic vision’, writes Majumdar, “than the fact that it was exactly 50 years afterwards, on February 23 1947, that Major Attlee, the then Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, announced in the House of Commons the decision of the British government to quit India.”

Throughout his tour across the Indian subcontinent, from ‘Colombo to Almora’, Vivekananda’s speeches manifested three aspects, they were, first “his sense of a supreme mission which almost appeared as a historical imperative”, second “his conviction of the indestructibility of the ‘Indian soul’ and the invincibility of Indian ‘spirituality'” and third was “nationalism which alone could become an effective and adequate instrument for the fulfillment of India’s destiny.”

These formed the bedrock of his philosophy of Indian nationalism. As Sri Aurobindo inspiringly and movingly observed: “The going forth of Vivekananda, marked out by the Master as the heroic soul destined to take the world between his two hands and change it, was the first visible sign to the world that India was awake not only to survive but to conquer.” It was that keynote of the Swami’s message which brought about a decisive turn in India’s collective consciousness, imparting a definite turn to the struggle for freedom.

Speaking of Vivekananda’s contribution in igniting the flame of freedom and revolution in India, iconic French author and philosopher, Romain Rolland observed: “The Indian nationalist movement smouldered for a long time until Vivekananda’s breath blew the ashes into flame, and erupted violently three years after his death in 1905.”

That volcano in the Swami often erupted at the sight of the exploitation, subjection and degradation of his Motherland. As Sister Nivedita, in her timeless impressions of the Master, recollected that “there was one thing however, deep in the Master’s nature, that he himself never knew how to adjust. That was his love of his country and his resentment at her suffering. Throughout those years in which I saw him almost daily, the thought of India was to him like the air he breathed…He was born a lover, and queen of his adoration was his Motherland.”

Expressions of that resentment often spilt out in forceful words of indictment and condemnation on the condition of India. Writings to Mary Hale on 30th October 1899, Vivekananda spoke of the “terrible massacre the English perpetrated in 1857 and 1858, and still more terrible famines that have become the inevitable consequence of British rule (there never was a famine in a native state)” and how it killed millions of people. Passionately describing the sad state of affairs, Vivekananda told them of how the “freedom of the press [was] stopped already” and how “we have been disarmed long ago” and how “for writing a few words of innocent criticism, men are being hurried to transportation for life, others imprisoned without any trial; and nobody knows when his head will be off.”

Decades later, describing Vivekananda’s and his Master Sri Ramakrishna’s influence on the revolutionary movement, Sri Aurobindo recollected, that the “influence of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda worked from behind” as a result of which “the Movement and the Secret Society became so formidable that in any other country with a political past they would have led to something like the French revolution.”

In his pamphlet, ‘Bhawani Mandir’ — written anonymously while he was in the service of the Maharaja of Baroda, Sayajirao Gaekwad, around 1905 — Sri Aurobindo spoke of the ‘lion-heart’ Vivekananda. The pamphlet which laid out a structure of revolutionary action was smuggled out of Baroda into Bengal and other parts of India, and thousands of copies were made and distributed among the youth. “…What is it that so many thousands of holy men, Sadhus and Sannyasis, have preached to us silently in their lives? What was the message that radiated from the personality of Bhagawan Ramakrishna Paramhansa? What was it that formed the kernel of the eloquence with which the lion-like heart of Vivekananda sought to shake the world? It is this that in every one of these three hundred millions of men, from the Raja on his throne to the coolie at his labour, from the Brahmin absorbed in his sandhya to the Pariah walking shunned of men, GOD LIVETH. We are all gods and creators, because the energy of God is within us and all life is creation; not only the making of new forms is creation, but preservation is creation, destruction itself is creation.” Sri Aurobindo’s ‘Bhawani Mandir’ had electrified young India, and through it, Vivekananda’s message of India’s awakening rang forth.

Long ago, the British Intelligence had taken note of Vivekananda’s striking presence. A report on the Ramakrishna Mission by the colonial intelligence agencies in 1909 mentions that Vivekananda “first came to notice in 1892, when he was touring through the various States in Kathiawar and was entertained by some of the petty Chiefs…it was noted that he [Swami Vivekananda] took an interest in politics.” JC Ker, formerly of the colonial Criminal Intelligence Department in Kolkata, in his notoriously authoritative ‘Political Trouble in India (1907-1917)’ — a comprehensive record of revolutionary activities in the country during the early nationalist phase — wrote in exasperation of ‘anarchism’ and that it was “clear as noonday that the religious aspect of anarchism was merely an extension of that revival of Hinduism which is the work of Dayananda, Ramakrishna, Vivekananda…”

As early as 1906, Deenabandhu CF Andrews describing Vivekananda as an ‘Indian nationalist years before the great national movement’, saw a ‘rapid Hinduising of national ideas going on among the younger men, of the religious element getting mingled with the political’. He spoke of how ‘Young Bengal’ was “looking now to the ideals of Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda.” “Our students”, Deenabandhu Andrews noted, “are all reading cheap reprints of the latter’s works…”. Dunlop Smith, the then secretary to Viceroy Lord Minto, writing in 1908, on the impact of Swami Vivekananda and Ramakrishna, cautioned: “It will be serious if it proceeds to extreme lengths and actually reaches the masses.” In the course of decades that’s exactly what happened. In 50 years, India was liberated and Vivekananda’s influence and effect had been ceaseless.

As Sri Aurobindo described it, ‘Vivekananda was a soul of puissance if ever there was one, a very lion among men, but the definite work he has left behind is quite incommensurate with our impression of his creative might and energy. We perceive his influence still working gigantically, we know not well how, we know not well where, in something that is not yet formed, something leonine, grand, intuitive, upheaving that has entered the soul of India and we say, “Behold, Vivekananda still lives in the soul of his Mother and in the souls of her children.”

Vivekananda continues to live on in the soul of free India.

(The writer is a member of National Executive Committee (NEC), BJP, and the Hony. Director of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal)

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)