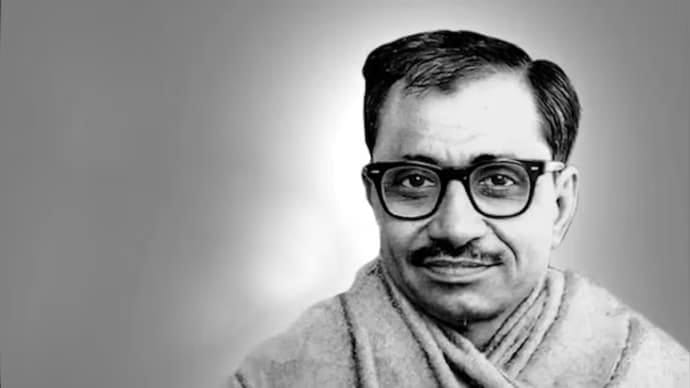

In the age of ideological borrowings from the West, where capitalism and socialism competed to shape post-colonial nations, one Indian thinker dared to present a home-grown alternative rooted in Indian ethos: Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya. His philosophy of “Integral Humanism” (Ekatma Manav Darshan) wasn’t merely a political manifesto; it was a civilizational articulation of India’s soul—an indigenous framework seeking harmony between body, mind, intellect, and soul; between individual and society; between tradition and modernity.

Deendayal Upadhyaya was born on 25 September 1916 in Nagla Chandraban, a small village in Uttar Pradesh. Orphaned at a young age, he grew up under the care of his maternal relatives, facing severe economic and emotional hardships. Despite these challenges, he excelled academically and intellectually. His early brush with Indian scriptures, coupled with his exposure to nationalist thought through the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), shaped his deeply rooted cultural worldview. These experiences were not just educational but transformative, instilling in him the resolve to think beyond the binaries of left and right and to craft an Indian model of development. Presented in a series of lectures in 1965, Integral Humanism emerged as a third way that challenged both the materialism of the West and the dogma of the Marxist Left. The core tenets included: i) Holistic View of Man: Upadhyaya rejected the reductionist view of man as merely an economic unit. He envisioned man as an integration of body, mind, intellect, and soul.

True progress, therefore, must elevate all aspects of the human personality. ii) Dharma-Centric Society: Not religion in the narrow sense, but dharma as an ethical principle guiding individual and societal conduct. Dharma ensured balance and responsibility. iii) Decentralized Economy with Swadeshi Ethos: He advocated for economic systems based on local needs and indigenous models, promoting self-reliance and dignity of labour, rather than centralized industrialization driven by Western models. iv) Antyodaya: The upliftment of the last man. Unlike Western welfare models focused on class warfare or elite benevolence, Antyodaya called for empowerment rooted in empathy and duty. v) Cultural Nationalism: Upadhyaya believed national identity must be rooted in cultural continuity. India, as a nation, was not born in 1947 but had a civilizational essence that must inform its policies. In the mid-1960s, in a dusty village of Ballia district in Uttar Pradesh, a young farmer named Ramprasad faced a crisis. His land was parched, monsoons had failed, and his children were dropping out of school. Government schemes existed only on paper, and migrating to the city seemed the only option. A local group of Bharatiya Jana Sangh karyakartas, inspired by Upadhyaya’s philosophy, decided to intervene. Instead of handing out aid, they worked with villagers to clean an old pond, introduced water-harvesting techniques, and set up a community grain bank. A local school was revived with volunteer teachers, and a collective farming initiative began.

Over the next few years, the village not only stabilized but flourished. The key difference? The villagers felt ownership over their destiny. Ramprasad would often tell visitors, “We didn’t get help; we got wisdom.” This transformation exemplified Integral Humanism in action: self-reliant, value-based, community-driven. What set Integral Humanism apart from contemporary ideologies was its refusal to be boxed into Western political binaries. It did not glorify the state (as in socialism) nor did it idolize the market (as in capitalism). Instead, it posited that society was the coreunit, with both state and market playing facilitatory roles. Upadhyaya’s thought was anticipatory of many modern challenges. Long before the environmental movement gained traction, he spoke of harmony between man and nature. Decades before sustainable development became a UN goal, he was advocating for localized, culturally aware economic systems. His emphasis on ethical politics, decentralization, and value-based education resonates even more powerfully today.

Today, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) formally upholds Integral Humanism as its ideological foundation. Policies like “Atmanirbhar Bharat,” rural self-reliance, promotion of traditional knowledge systems, and focus on the last-mile delivery can trace their philosophical roots to Upadhyaya’s vision. But beyond politics, Integral Humanism offers India a unique lens to look inward while stepping outward. As the world reels under the excesses of globalization and consumerism, Upadhyaya’s call for ethical living, spiritual anchoring, and holistic progress appears not archaic but urgent.

Deendayal Upadhyaya’s Integral Humanism is not a relic of the past but a compass for the future. It offers India a model of development that is culturally grounded, socially inclusive, spiritually uplifting, and economically sustainable. It invites us to envision a civilization that doesn’t just compete but contributes, that doesn’t merely exist but enlightens. As India aspires to become a global leader, the wisdom of Upadhyaya urges us not to lose our soul in pursuit of power. Because in the final analysis, true progress is not measured by GDP alone, but by the dignity, harmony, and inner fulfillment of every human being. And in that vision, Deendayal Upadhyaya remains not just relevant, but revolutionary.

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)