Both Syama Prasad and Bose were fiercely and staunchly concerned and connected with the fate and destiny of Bengal and Bengalis and yet, had a clear vision of India’s greatness, a vision that was national, pan-Indian and global.

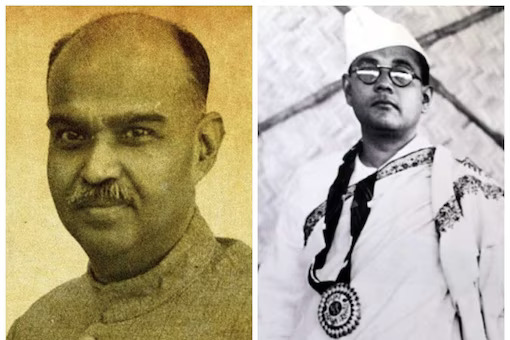

As India commemorates Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee’s 122nd birth anniversary and as one sees his dream and hopes for a free India being realised comprehensively, I look back in tribute to two of India’s and the state of Bengal’s greatest sons and patriots who were contemporaries and visionaries, each nurturing the dream of a great India in their innermost thoughts and outward actions.

To write in detail about Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee would be to delve deep into a very complex period of Bengal’s and of India’s history. Both Dr Mookerjee and Netaji, the latter, perhaps to a greater degree, continue to evoke strong emotions, especially in their beloved province Bengal, which was also the principal base of their political action.

While Dr Mookerjee’s legacy and contributions are still percolating the mass mind of India, Netaji’s contributions to India’s regeneration have percolated much more deeply and widely. Since 2014, Netaji’s legacy has seen, for the first time since India’s independence, a respectful reinstatement in our national life under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s leadership. The most recent, among a plethora of national tributes to Netaji, was the installation of a grand statue of his, at the head of Kartavya Path in New Delhi and instituting of a national award, for the first time, in his name. This was an aspiration and demand that was made by countless Netaji admirers over decades. In its fulfillment, the deeper and fundamental significance of his contribution to India’s freedom struggle has been publicly acknowledged by a grateful nation.

The abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir and the state’s increased pace towards comprehensive development, the successful conclusion of the G20 meet in Srinagar and a vastly improved law and order situation is perhaps the greatest tribute to Dr Mookerjee on his 70th death anniversary, which was on June 23. The essence and truth of his final struggle has been vindicated. Prime Minister Modi’s sturdy and steady political will, the Jana Sangh’s and the BJP’s relentless championing of the demand for abrogation of Article 370, and the persistence of generations of political activists and leaders led to the Article’s deactivation. It was a demand for which Dr Mookerjee had laid down his life in 1953 at the age of 52.

Netaji’s sacrifice was for India’s independence; Dr Mookerjee’s sacrifice was for preserving India’s unity and integrity, for its freedom and future. His prognosis of India’s security scenario and challenges, if integration was not cemented and final and if the separatist mindset was allowed free reign, came true in Kashmir in the decades that followed his death.

The legacy of both these iconic stalwarts underwent a period of marginalisation. Their political and ideological opponents made a strong and motivated effort over decades, especially after independence, to erase their contributions, to dilute the memory of their public actions and their many-sided contributions to our national life. They did this because both Dr Mookerjee and Netaji were fiercely independent and articulated determined positions which these political forces did not agree with. The Congress and the Communist parties were at the forefront of trying to erase their legacies.

The Communists heaped insults on Bose and Syama Prasad during their lifetime as well. While the communists equated Syama Prasad to the notorious Lord Curzon, for his advocacy of Bengal’s partition in 1947 and the need for the creation of a Hindu majority province of West Bengal as an integral part of the Indian union, Bose was castigated and labelled as a ‘quisling’ and the ‘henchman’ of Japanese imperialism. To the communist’s motivated campaign likening his demand to that of Curzon’s plan to partition Bengal four decades earlier, Syama Prasad responded by saying that “Lord Curzon’s partition and our demand for a new province are like poles asunder. The Curzon partition was aimed at giving a death blow to the ‘seditionist’ Bengali Hindus…Our present proposal for Hindu Bengal on the other hand is aimed at saving Bengali Hindus and also the cause of nationalism which is their life-blood.”

The Communist Party of India’s mouthpiece ‘People’s War’, for instance, continuously churned out insulting pieces on Bose, where it termed the Indian National Army (INA) as a mercenary army of ‘rapine’ and ‘plunder’. Heaping abuse on Bose became the favourite pastime of the Communists. Naturally, the People’s War received generous patronage from the British colonial administration. Sales of the mouthpiece, which came in five languages in addition to six regional language newspapers, shot up by 124 percent. The total circulation reached 65,000 copies, which was a huge number for wartime standards.

Of Bengal’s fate, many lamented when Syama Prasad passed away, that in an interval of about eight years, between 1945 and 1953, the province and its people lost two of its greatest and most dynamic sons, Subhas Chandra Bose and Syama Prasad Mookerjee. The former disappeared in August 1945 after an alleged plane crash in Taipei, while the latter met his end in Sheikh Abdullah’s sub-jail in Srinagar in June 1953, beyond the reach of India’s Supreme Court, lured into captivity, in a joint operation, planned and executed by the Sheikh and Jawaharlal Nehru.

The emotion or the mind space that both Dr Mookerjee and Netaji evoked and occupied in the Bengali psyche is perhaps best illustrated by a letter of gratitude that one of Bengal’s most iconic poets, Kazi Nazrul Islam, wrote to Dr Mookerjee in July 1942. Poet Nazrul was ailing and despite his family members seeking help from a number of leading Muslim figures of the era such as Fazlul Huq, then Premier of Bengal, Kwaja Nazimuddin and Hussein Suhrawardy, they had to return with empty platitudes. Dr Mookerjee, then Bengal’s Finance Minister in the Syama-Huq coalition ministry, on hearing Nazrul’s acute distress, rushed to his rescue. Not only did he support his treatment but also arranged for Nazrul and his family to spend months convalescing at the Mookerjee’s country retreat in Madhupur, then in Bihar, now in Jharkhand. A grateful Nazrul wrote to him, on how he respected him most among the members of the coalition ministry. But the poet’s most moving lines were reserved for both Dr Mookerjee and Netaji, when he wrote, “I know that it is we who shall completely free India, and on that day, [when India will be completely independent], Bengalis will remember you and Subhas Babu, before everyone else, you will be the true leaders of this nation.” Nazrul voiced the emotions of millions of Netaji and Dr Mookerjee’s compatriots.

In those difficult years, when Bose had undertaken a daring journey to continue the struggle to free India from foreign shores, Syama Prasad held the fort, especially in Bengal. The late Rabindra Kumar Dasgupta, well-known littérateur, cultural commentator and author, noted, that in those dark and difficult days, when the entire national leadership of the freedom movement was imprisoned, following the Quit India demand on August 9, 1942, Syama Prasad was the only voice of the struggle of Indian nationalism. It was he who upheld the ideals of the August Movement before the whole of India and the world. Within just about three months from August 1942, Syama Prasad would resign from the Bengal cabinet, having exposed the British administration’s and the bureaucracy’s perfidy in trying to crush the nationalist sentiment. His huge effort in support of the Midnapore revolutionary groups and gigantic effort in organising the largest non-official relief for victims of the Bengal famine in 1943, propelled him as the most decisive voice on the political firmament of not only Bengal but the whole of India. In those extremely trying times, Syama Prasad was “faced with two major problems that affected life, liberty and happiness of the people of his province.” The first was the “policy of the ‘Scorched Earth’ which was adopted early in 1942, and was applicable only to areas on the eastern border and eastern coastal regions of the country; this led to a great hardship and to the terrible famine of Bengal in 1943.” The other “was the highly oppressive measures adopted in the district of Midnapore to suppress the popular rising of the ‘August Movement.’” “During this dark and trying period,” writes, R.K. Dasgupta, “Syama Prasad’s staunch and undaunted voice was our only solace…” In a sense, Syama Prasad filled the void that Bose’s physical absence had generated in the mind and heart of young Bengal.

Swami Vivekananda’s and Sri Aurobindo’s deep influence on Bose clearly emerges from his letters. In his spiritual quest and early political quest, both Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo played a major formative role in his life. In one of his letters, he writes, “Swami Vivekananda died in 1902 and the religio-philosophical movement was continued through the personality of Arabindo Ghose. Arabindo did not keep aloof from politics. On the contrary, he plunged into the thick of it, and by 1908 became one of the foremost political leaders. In him, spirituality was wedded to politics…” In another letter, young Bose, about to take the plunge into public life and dedicate himself to the cause of India’s freedom, writes, “Arabindo Ghose is to me my spiritual guru. To him and to his mission I have dedicated my life and soul. My decision is final and unchangeable.”

Sri Aurobindo’s influence on Syama Prasad was no less. During the most trying times in Bengal when Syama Prasad struggled to ward off the communal politics of the Muslim League, he found support from a number of Sri Aurobindo’s disciples and adherents who sided with him under the indication of their spiritual master. The first commemorative plaque naming the Cell in which Sri Aurobindo was imprisoned in the Alipore Jail between 1908 and 1909, was installed by Syama Prasad after independence. When it was decided to form a university as a memorial to Sri Aurobindo in 1951, Syama Prasad was invited by the mother of Sri Aurobindo Ashram, to preside over the Sri Aurobindo Memorial Convention which convened in Pondicherry to deliberate on the idea of an education centre dedicated to Sri Aurobindo’s vision.

As Swami Vivekananda’s influence on a youthful Bose was profound, so was the influence of the founder of Bharat Sevashram Sangh, Acharya Pranavananda on Syama Prasad. The youthful Acharya looked upon Syama Prasad as the saviour of the Hindus of Bengal and India. Swami Pranavananda’s interactions with Syama Prasad, his public endorsement of Syama Prasad’s struggle for the security and future of Bengal’s Hindus then oppressed by Muslim League rule, his indication of Syama Prasad as the one who will stand up for the Bengali Hindus, was a very interesting and inspiring public partnership between a widely revered young Hindu saint and one of the most popular young Hindu leaders of regional and national influence.

Of Syama Prasad’s relations with the Bose brothers, historian Leonard Gordon writes: “The Hindu Mahasabha was never strong as an organization in Bengal, but its leader, Shyama Prasad Mookerjee [sic], became a prominent and articulate spokesman for this point of view during these years. In 1929 he took over Sarat Bose’s Calcutta University seat in the Bengal Legislative Council and remained in the Council for many years. He was also a family friend of the Boses, though he differed from them on many political issues. He would fight to get them out of prison and press the government with questions about their health when they were in prison…”

When Bose led the historic movement demanding the removal of the Holwell Monument in July 1940, terming it as a symbol of India’s humiliation and slavery that stood at the heart of Calcutta for 150 years, the colonial police launched a severe and violent crackdown. He was arrested along with several others. While he led the movement outside, Syama Prasad, in the Assembly vehemently protested against the police’s atrocities on students’ issuing a very strong and emphatic condemnation.

Though Syama Prasad and Bose’s politics differed on a number of occasions, especially on the communal question in Bengal, the Boses and Syama Prasad came together in Bengal’s interest whenever the need arose. For instance, when the Muslim League government sought to introduce the Secondary Education Bill which would completely push Bengal’s education system and apparatus under the control of the League-nominated Muslims, Syama Prasad opposed the move. He received support from Sarat Bose, then leader of the Congress Party in the Legislative Assembly, who, while supporting him, cautioned the government against tampering with secondary education. The Bill was eventually rejected having been discussed in the Assembly for four years. This was a major victory for Syama Prasad.

An entry dated February 2, 1939, in Syama Prasad’s diary describes his strong disappointment with Mahatma Gandhi’s opposition to Bose’s re-election as Congress president for a second term. “In train. Read Gandhi’s statement on Subhas Bose’s election carefully. I cannot conceal my disappointment at its tone and content. Why should he be so upset at Subhas’s victory? After all it was he who made him President last year. And if he honestly feels that Subhas has failed, he should let the public know why he so thinks – at any rate he must open his mind to Subhas at least…what right had they to state behind Subhas’s back. They (including Gandhi) had decided that it was unnecessary to re-elect him and what is more, that S’s election would be harmful to the interest of India. After all, Subhas was still the President and if a large section of Congress people wanted him to seek re-election, there was nothing very serious about it…This is not Democracy but a low type of Fascism!”

In early November 1945, under Syama Prasad’s leadership, the Hindu Mahasabha successfully observed INA Day all over the country in support of the patriot-soldiers of the INA, and their strongly worded appeals proved effective. A popular upheaval in Calcutta took place on 21-23 November when a student procession demanded the release of INA prisoners and a violent clash between them and the police appeared to be inevitable. The situation was salvaged by Syama Prasad through his timely and fearless intervention. He was held in high esteem by the students as their friend, philosopher and guide.

October 21, 1951, selected by Syama Prasad for the launch of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh was a conscious decision to coincide the historic occasion with the founding day of the Azad Hind government by Bose in 1943. Addressing a large public meeting in Delhi on the evening of October 21, Syama Prasad recalled that Bose had declared the Azad Hind government on that very day and hoped that Bharatiya Jana Sangh would carry on the fighting tradition of the INA in the service of the country.

Both Bose and Syama Prasad were unique in their ways, each representing a strand and dimension of politics, philosophy, national service and liberation, that had their space and necessity in the decades and years that preceded and followed India’s independence. Both were fiercely and staunchly concerned and connected with the fate and destiny of Bengal and Bengalis and yet, had a clear vision of India’s greatness, a vision that was national, pan-Indian and global. They could situate Bengal in the larger vision of India and its future. While Bose shook the British Empire to its roots and hastened the day of India’s freedom through his worldwide actions, Syama Prasad ensured that portions of Bengal, Punjab and Assam were forever integrated into free India. Later, in a larger sphere, Syama Prasad’s struggle for India’s complete integration cemented India’s unity and freedom.

Each was recognised as Bengal’s tallest leader in their age and times, and each had a profound acceptance among Bengal’s leading minds and thought-leaders, especially among those who contributed, in no small measure, to the creation of the Bengali imagination and cultural aspirations. Each left behind a lasting impression on India’s national life. It is not fortuitous or by chance that the political stream that Dr Mookerjee founded — Bharatiya Jana Sangh — and which grew into a mighty flow as Bharatiya Janata Party, over the decades, is the same political stream that has reinstated Netaji’s legacy forever in India’s national life and ethos. Even in their legacies, each has paid tribute to the other. It is this convergence, this synergy and assimilation that must inspire us in our march in ‘Amrit Kaal’ towards realising the vision of India that both Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose cherished, nurtured and struggled for.

The writer is Director Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, Member, BJP, National Executive Committee, Member of the National Committee for Netaji’s 125th Birth Anniversary. Views expressed are personal.

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)