By Dr. Ananya Awasthi

Government of India recently announced the new National Health Policy 2017. This new policy marks a watershed in the history of healthcare policy making in India. As healthcare seeking citizens, let us go through the main highlights of the policy to better understand how it affects our lives and health. Once we equip ourselves with the lasts trends and research on health care needs in India and what this policy has to offer, we can sure make our own informed judgements on whether or not it marks a watershed.

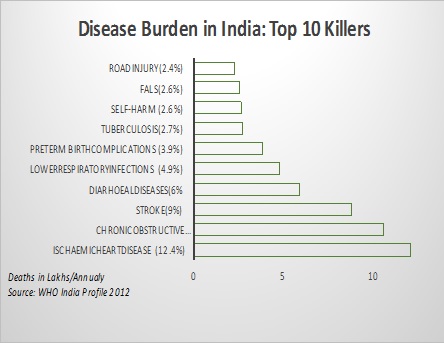

Shift of Focus from Communicable to Non-Communicable Diseases and Lifestyle disorders

Classically, India has been perceived as a hub for infectious diseases, maternal and new-born mortality and life-threatening epidemics. What you would be surprised to know is that as of today, the three top killers in India are not Tuberculosis and maternal deaths but are heart disease (12 lakh deaths annually), lung disease (10 lakh deaths annually) and stroke (9 lakh deaths). What is rather odd is that the past healthcare policies have nearly ignored the rising epidemic of Lifestyle Disorders and Non- Communicable Diseases. This is when WHO estimates that Non-Communicable diseases (with mostly preventable risk factors) account for 60% of all deaths and significant morbidity in India[1]. Instead recurring investments in pet areas like Maternal & Child Health & HIV have diverted a major portion of public investments to a handful of vertical programs. For example, if we analyze the approved outlay for National Health Mission 2015-16, nearly 4,568 crore were allotted for Reproductive & Child Health whereas the National Program for Prevention and control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases and stroke (NPCDCS) managed to receive a meagre 235 crore![2] While we cannot be complacent about the need to focus on these areas as well, the new health policy rightfully signifies a shift in the public discourse to address the dominant burden of NCDs & lifestyle disorders.

Reducing financial burden due to out of pocket expenditures on health

In the previous healthcare policies, there has been an obvious disconnect between the understanding of health & healthcare financing. What is most intriguing is the little focus that household spending on health and catastrophic expenditures have received. After all healthcare to a lay Wo(Man) boils down to how much s(he) pays for health? Though this might be the result of a false sense of assurance that we have been given by a statist model of public health care delivery.

Data from NSSO, Ministry of Statistics show that out of every 100 INR spent on health by each one of us today, nearly 67 INR are paid out of our own pockets and less than 30 INR are taken care of by the so-called socialist public systems.[3] Further, research shows that each year nearly 6 crore people are pushed to below the poverty line due to catastrophic healthcare expenditures despite the tall claims of state led healthcare delivery. [4]The new national health policy, timely takes account the “inability to cover the entire spectrum of health care needs, through increased public investment [that] has led to a rise in the out of pocket expenditure and consequent impoverishment”. And as an answer to this scenario, it calls for progressive Universal Health Coverage through Financial Protection. This also aligns with the WHO model which sees financial protection from catastrophic healthcare expenditure as one of the most important pillars for Universal Health Coverage. Moreover, the government commits itself to increasing the investment in the healthcare sector from a current 1.15% of the GDP to 2.5% of the GDP by 2025, thus increasing the bandwidth for spending on healthcare.

Universal Health Coverage & Health Insurance

Relying solely on public delivery of services and ignoring the case of collaborating with the not for profit/private health care providers has created a situation where as high as 86% of rural population and 82% of urban population are not currently covered under any scheme of health expenditure support.[5] As a result of which poor households especially those belonging to the SC,ST and backward communities have to rely on their life long savings and borrowings to finance the healthcare costs, in the absence of any social safety net or nationwide insurance models. Moreover, quite contrary to the perception that private healthcare options are not available to the poor or in rural areas, national survey shows that more than 70% (72% in rural and 79% in urban) spells of ailment are indeed being treated by the private sector.[6]

Hence the new policy positions the government as a “strategic purchaser” of healthcare where improved access and affordability, of “quality” secondary and tertiary care services is provided through a “combination of public hospitals and well measured strategic purchasing of services in health care deficit areas, from private care providers, especially the not-for profit provider”. Instead of the commonly cried rhetoric of “privatization of health care”, the New Health Policy in fact seeks to purchase these services on behalf of its citizens, thereby ensuring equity in access to quality care for all irrespective of their social backgrounds and ability to pay.

It is particularly aimed at reducing inequities in access to quality of care wherein members of the SC, ST, Tribal community and poor households are provided with a “choice” to access high quality care both from the public & private facilities. This in turn is expected to have a domino effect on the public facilities which are incentivized to improve their “efficiency” and “quality” in light of increased “competition”. Another expected outcome of this policy is to retain the central role that public health systems play in delivering primary health services while in areas where district hospitals are not equipped to provide specialized care, inclusive partnerships with the private/not for profit sector are forged to provide high quality, secondary & tertiary care.

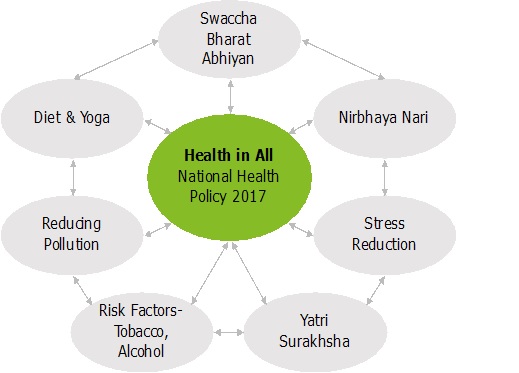

Focus on Social Determinants of Health & Multi-sectoral Action

A medical approach to health as adoptedby previous health policies, has invariably restricted the scope of healthcare policy making to the ministries of health. Research from all over the world is increasingly highlighting the big role that a multitude of other factors like public health & sanitation, poverty reduction, gender empowerment, health diets & yoga, risk factors like Tobacco, Obesity, Diabetes& the subsequent behavioral choices play in determining our final health outcomes. This has even led the WHO to adopt the model of “Social Determinants of Health” as a guiding framework for policy implementation worldwide. Hence the new health policy seeks to drive a multi-sectoral approach for health care where “Health for All” is complimented by “Health in All” policy framework.[7] This will translate to the much-needed cross coordination between each of the 7 listed verticals and various ministries/sectors of Public Health; all culminating to a Swasth Nagrik Abhiyan –a social movement for health.

Thus, a finer reading of the health policy will make it clear that the National Health Policy 2017, justifiably reflects the change in disease trends, prioritizes financial security against healthcare expenditures, signals the coming of an insurance era and prepares us for a nationwide program on progressive Universal Health Coverage. Conversely, instead of taking a short cut and declaring health as a justiciable right without even having the capacity to deliver services, this health policy actually lays out a realistic road map for the strategy to be followed to realize the inclusive dream of “health assurance” for each and every citizen of India.

References:

[1] World Health Organization, Non-Communicable Diseases (Ncd) Country Profiles 2014. Pg.91

[2]Outcome Budget 2015-16 For Department Of Health And Family Welfare

[3] National Sample Survey Office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of IndiaKey Indicators of Social Consumption in India Health, NSS 71st round (Jan-Jun 2014)

4]Berman.P et.al, The Impoverishing Effect of Health Care Payments in India, Economic & Political Weekly (EPW), Vol XLV, No. 16, 2010. Pg. 65

[5]National Sample Survey Office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, Key Indicators of Social Consumption in India Health, NSS 71st round (Jan-Jun 2014)

[6] National Sample Survey Office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, Key Indicators of Social Consumption in India Health, NSS 71st round (Jan-Jun 2014)

[7] Health in all policies: Helsinki statement. Framework for country action. WHO 2014

(The author is an expert in public policy and health and has been working and writing on these issues)

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)