The success of Chandrayaan-3 mission is a culmination of India’s deep-rooted scientific temper which has defied all attempts aimed at subduing it.

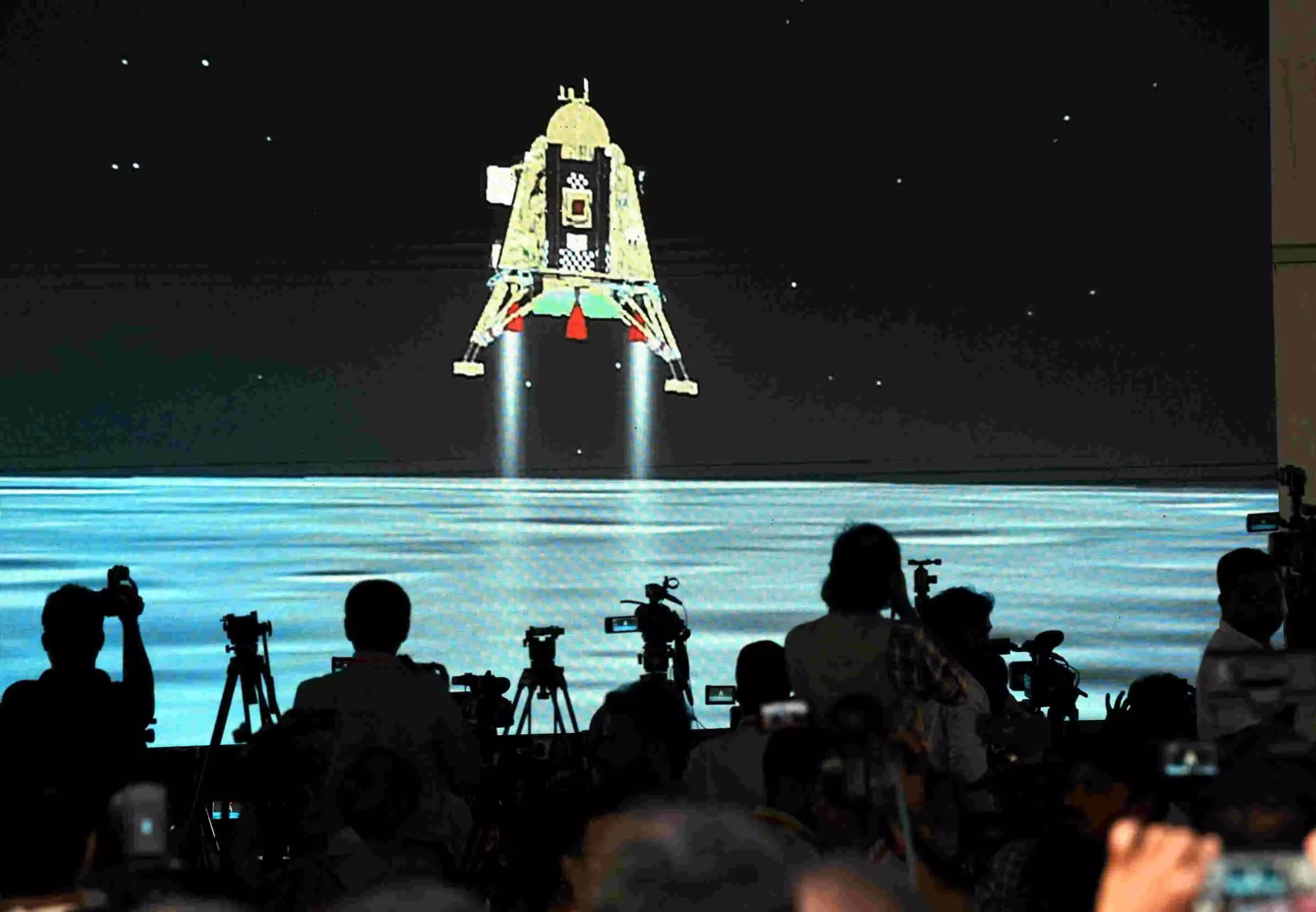

This last week has been an action-packed week in many respects, clearly indicating that the India of Amrit-Kaal rises driven by determination, confidence and a resolve to forsake and dissolve the colonial-mindset. As Chandrayaan-3 landed, finally placing India on the moon, it became evident that India had made a giant leap of decades and finally achieved one of the most defining feats in Amrit-Kaal. In his address to the ISRO scientists, Prime Minister Modi rightly said that this was one of the defining moments of this century, a moment that has become immortal in the collective memory of humankind, and of India in particular.

From being stonewalled once with an acute and motivated technology denial, from being kept out of a self-ordained elite club of tech-powers who monopolized and controlled technology growth and dissemination, from being treated as a country which could not be trusted with technology, India has emerged with great aplomb on the global science-tech scene as a country to look forward to, as a reliable partner in technology dissemination in line with Prime Minister Modi’s call, of the need for knowledge-sharing so that future global challenges could be jointly tackled and resolved.

Prime Minister Modi also dedicated the success of Mission Chandrayaan and its achievements and discoveries to the countries of the “Global South’, which for long have had to face denial and control, despite yearning to emerge out of their colonial strait-jacket and wanting to push behind their past of exploitation and exaction. Like her philosophy and civilisational values, which has always been for the benefit of humankind, India’s science and her scientific discoveries and achievements are also dedicated to that same global ideal and aim, as PM Modi reminded the BRICS leaders and also reiterated in his thanksgiving address at ISRO.

Indeed, in mindset transformation and alteration, we have come a long way in the last decade. When PM Modi spoke of naming the Chandrayaan’s landing spot as “Shiv Shakti Point” – a nomenclature with a deeply philosophical essence, it became evident that these terms, expressions and words which carry a profound and positive essence, were no longer to be shunned in our public and governance discourse.

The Visva Bharati University Bill debate in Parliament in May 1951 came to mind. It was the first case on how an independent India, as a constitutional republic, under the Nehruvian dispensation, displayed an aversion, an allergy to any allusion to India’s philosophical core and essence. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, as Union Education Minister, while piloting the Bill wanted to do away with Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore’s defining motto for the University which said, “In the name of one Supreme Being who is Shantam, Shivam, Advaitam.” Taken from the Mandukya Upanishad, Tagore wanted to signify that his educational experiment – Visva Bharati – which spoke of the world gathering in a nest, was a university which was different from the rest, in that it espoused shaping of minds that would also look and connect to the core, to the soul, to the essence of subjects and of fields of study, reflecting India’s civilisational and spiritual world-view.

In fact, these words were chanted before every meeting, gathering and programme at Visva Bharati, and now, independent India’s first education minister wanted to do away with them. An intense debate ensued, MV Kamath, in a well-reasoned intervention, lamented that a ‘fetish’ was being made out of secular state, and Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee, who had a special relationship with the University and with Gurudev for over decades, while participating in it, made a point which remained strikingly resonant for all these years, ‘What was the hesitation’, he asked, ‘in putting those words in the Act? I have not been able to discover any reason. Again, while you put it in the schedule, you deliberately omit the last few words. Why have you done it? I have been asking myself, and I would appeal to Maulana Sahib to look into the matter more carefully and if possible, revise the decision which he has taken on behalf of the Government. What is it that we are afraid of? Is it because we have said that ours is a secular State, we should not mention Supreme Being anywhere in any constitutional document?’

That ambivalence has now eroded, from placing the Sengol in the new Parliament, to the Adheenam’s blessing in its reinstatement, to the revision of British era laws and introducing Bharatiya nomenclatures, to the Prime Minister liberally citing from the scriptures, I believe we are seeing the coming of an era, which was fairly common and accepted in India’s public life in the past but which had been demonised, post-independence, because of the pressures of Nehruvian secularism and its idiosyncrasies and fetishes.

The Mission Chandrayaan’s success, PM Modi’s call of ‘Jai Vigyan, Jai Anusandhan’, also brings to mind the struggles of the past of India’s leading scientific minds to rekindle India’s scientific tradition and mindset amidst colonial subjection. The inspiration imparted to Jamsetji Tata by Swami Vivekananda to set-up a ‘Research Institute of Science for India’ is well-known. Jamsetji Tata had requested Swami Vivekananda to take the lead in rousing public opinion in its favour. The Swami had to decline any express involvement because of his preoccupation with building the monastery at Belur and because of indifferent health, but he indicated his full support behind the idea.

Tata, along with his assistant Burjorji Padshah, writes author Kunal Ghosh, in his ‘Unsung Genius: a Life of Jagadish Chandra Bose’, then met Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India in 1898, for discussing the proposal. Curzon, as was his wont, “summarily shot down the project on the specious ground that Indians were incapable of achieving real mastery in science”. Curzon had the gumption to say this knowing well of Jagadish Chandra Bose’s recognition in Europe, as ‘an eminent scientist’ three years prior to this and of his first scientific tour of three European countries, two years before this meeting took place. In fact, William Ramsay, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1904, had derisively told Bose, “You are an exception. One swallow does not make a summer.” Ramsay, then, a dominant mind in the Western scientific world, who had much say in shaping colonial scientific policy, exuded a race prejudice and sided with Curzon in his rejection of the scheme.

A deeply disappointed Jamestji sent his sister and Padshah to meet Swami Vivekananda in 1899 in Calcutta to discuss the issue. “They sought help from the Swami and it was given in full measure.” Prabuddha Bharata, the flagship English newsletter of the Ramakrishna Mission which was already being widely acclaimed, then published from Madras, carried an appeal by Swami Vivekananda himself in support of “Jamestji’s decision to defy Lord Curzon’s will” and to go ahead with the project to promote, nurture and rekindle India’s scientific talent.

In his appeal, Swami Vivekananda spoke of not being “aware if any project at once so opportune and so far-reaching in its beneficent effects was ever mooted in India, as that of the Post-Graduate Research University of the Tata.” It was a scheme, the Swami argued, which, “grasps the vital point of weakness in our national well-being with a clearness of vision and tightness of grip, the masterliness of which is only equal by the munificence of the gift with which it is ushered to the public…” Vivekananda’s appeal concluded with the following words forcefully articulated in print in defiance of the attitude of the colonial masters, “We repeat no idea more potent for the good of the whole nation has seen the light of the day in modern India. Let the whole nation therefore, forgetful of class or sect or interests join in making it a success.” Swami Vivekananda’s appeal in support of Indian science thus, generated waves across the Indian intelligentsia and the thinking public.

Following this, Sister Nivedita, one of the most active advocates of India’s scientific prowess, a pillar who stood by and supported the scientific endeavours and struggles of the likes of Jagadish Chandra Bose, “wrote several articles in the Statesman supporting the Tata project and wrote to many British educationists. There were also others who bolstered the campaign.” The points and counterpoints continued with forceful advocacy for the scheme and for allowing India’s scientific spirit the scope for emerging. This phase was symbolic and marks the beginning of India’s struggle, in modern times, to achieve parity, independence, equity and power in the quest for science and knowledge. The national education movement that soon followed this episode gave further boost to that demand and aspiration.

In a sense, with Chandrayaan-3’s landing in the south pole of the Moon, a region which has never been frequented before, another phase of that struggle has achieved successful and victorious completion. It is also a tribute to the likes of Bose, Raman and PC Ray, who through decades of struggles kept up the hope of India’s scientific triumph alive, who insisted on projecting India’s past civilisational scientific achievements and also of proving her capacities in modern science through repeated scientific experiments and success in various fields.

“If I could, for a moment command the organ-voice of Milton,” once wrote Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray, one of the fathers of India’s modern scientific quest, “I would exclaim that we are of a Nation not slow and dull, but of a quick, ingenious and piercing spirit, acute to invent, subtle and sinewy to discourse, not beneath the reach of any point the highest the human capacity can soar to. Therefore, the students of learning in her deepest science have been so ancient and so eminent among us that writers of a blest judgment have been persuaded that even the School of Pythagoras took the cue from the old Philosophy of this land…”

India’s Moon-landing has demonstrated that India’s achievements are indeed “not beneath the reach of any point the highest the human capacity can soar to.”

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)