By Anish Gupta

- The presence of a high amount of counterfeit currencies in the Indian economy was one of the principal reasons cited by Prime Minister Modi while doing away with currency notes of high denomination from the midnight of November 8, 2016. The rationale behind this move has been questioned by many scholars, politicians and the media fraternity, who believe that the quantity of counterfeit currency was not at an alarming level for any government to take a step as big as demonetization.The recent policy of demonetization has apparently targeted the realtors, hoarders, black marketers, illegal trade, funding of terrorist, hawala transactions etc. Implementation of the policy of demonetization, however, does not block the possibility of other measures or policy decisions that government could undertake to tackle other forms of black money. In fact it has provided a foundation for anti-black money drives and has created a fear in the mind of people involved in corruption.

The data on withdrawn currency notes deposited in banks till December 30, 2016, can help government identify the individuals who evade income tax. Hasmukh Adhia, the union revenue secretary, in an interview to a national daily (Indian Express February 3, 2017), mentioned that a set of puzzling figures emerged from the database of deposits till December 30, 2016, which hints towards tax evasion at a larger extent. According to him, the bulk of deposits made after demonetization in terms of banned notes of 500 and 1000, were of those above Rs 2 lakh. As people thought a deposit of Rs 2.5 lakh could be safe, so most of them deposited around Rs 2.25 lakh (deposits) in 10-15 accounts. A lot of cases were found where 20 accounts were connected to a single PAN.

During the period of demonetization, deposits of amount between Rs. 2 lakh and Rs 80 lakh, were deposited in 1.09 crore accounts, and deposits of over Rs 80 lakh were entered into 1.48 lakh accounts.It can be clearly contrasted with the figures on income tax returns filed in 2015-16, which indicate only 76 lakhs individual assesses have declared their income above Rs. 5 lakh. The number of people showing income more than Rs. 50 lakh in the entire country is only 1.72 lakh.

However, the main intention of writing this piece is not to evaluate the effects of the policy of demonetization on the Indian economy, which is difficult to measure in its entirety at this juncture, but to point out misplaced data on counterfeit currency used for a purpose to settle political scores, not just by some politicians inside or outside parliament, but also by some of the most respected academicians in various journals of repute, to counter government’s claim that substantial amount of fake currencies existed in Indian economy especially in large denomination.

It is not much known to the common readers that how some academicians and some journals as reputed as the Economic & Political Weekly (EPW), have indulged in misleading the nation on the figures related to counterfeit currency notes, just for the sake of criticizing the current government. As much as 5 editorials and more than 15 articles were published in the EPW, dedicated to views against demonetization, except for one. Though writing against any policy or view is very much accepted in democracy, the problem arises when the counter views are conveniently suppressed in a very sophisticated way by the print media as they are owned by some few elite belonging to a particular ideology. Interestingly the lone article (Gupta, 2017) which questioned the usage of misplaced data to belittle the amount of counterfeit currency specifically in an article—‘Demonetisation: 1978, the present and the aftermath’ (EPW, 26 November 2016), was given space only in ‘web exclusives’ section (not in printed version). Moreover, this article was deliberately kept out from the list of articles shown on ‘web exclusives’ page of EPW site for a long time. Though, other articles published before and after it can be seen in the list. Effectively the article was published while ensuring that it doesn’t get any currency/readership.

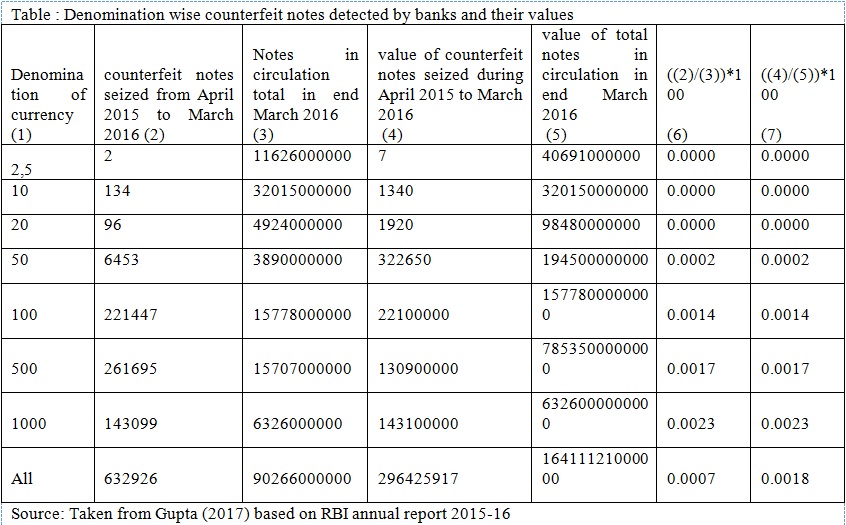

On the issue of counterfeit currency, an article written by Rajakumar[1] and Shetty[2] (2016, EPW), went on to say, “Counterfeit notes have generally constituted less than or around 0.002% of notes in circulation”. This claim was made on the basis of Table VIII.8 of RBI Annual Report. Gupta (2017) tried to point out how the above mentioned article (even many others), cited RBI figures on counterfeit currency in a misplaced manner ignoring four crucial points; First, difference between volume and value of counterfeit currencies. Second, difference between volume/value of counterfeit currencies in circulation and volume/value of counterfeit currency seized in a particular year. Third, impossibility of estimation of counterfeit currency in Indian economy due to attached illegality with the same. Fourth, misleading ratio of counterfeit currency with total currency in circulation.

Ignoring the difference between the volume of counterfeit currencies and value of counterfeit currencies may produce misleading results, since both are different, and the difference between these two increases with increase in the denomination of counterfeit currency. Similarly, what authors were calling the ratio of counterfeit notes to total notes in circulation is actually the ratio of the value of seized counterfeit notes with the value of total notes in circulation. The ratio of seized counterfeit currencies with total currency in circulation is 0.0007, not 0.002 mentioned by the authors (see Table-1).

Even, the volume or value of counterfeit currencies cannot be estimated in any economy due to the sense of illegality attached with the same. Data on counterfeit currencies shown by RBI reports are highly underestimated, as it excludes currencies seized by police and other law enforcement agencies as well. Moreover, counterfeit notes that are still in circulation, which couldn’t be caught by the banking system, were not considered in the calculation, due to unavailability of the data. Apart from the issue of sense of illegality attached with counterfeit currencies, the number of unreported cases in the banking system are also very high as banks do not provide any credit for any reported case of counterfeit currency. And also due to a highly cumbersome process of reporting a matter to the police or any other government agency, people generally refrain from reporting such matters.

Gupta (2017) explains that even the use of the ratio of the total number/value of seized counterfeit notes by banks (FICN) with the total number/value of notes in circulation (NIC) as an indicator of extent of counterfeit currency is a misleading indicator. Though both NIC and total fake currency in the economy are stock, but FICN, which is being used as proxy of total fake currency by most scholars, is a flow concept calculated over a period of one year.Using this ratio of FICN to NIC as an indicator of the extent of fake currency in the economy is based on an unrealistic assumption that counterfeit currencies seized in a particular year comes into circulation in the same year, an assumption that points towards ignorance.

Given the impossibility of the estimation of the exact amount of counterfeit currencies in the economy, it will not be a correct premise to conclude that the level of fake currency is not alarming, just on the basis of counterfeit currencies seized by banks.

Most academicians and academic journals took the advantage of the ignorance of common readers who do not understand the difference between seized counterfeit currency and total counterfeit currency, and perceived data on seized counterfeit currency as total counterfeit currency. Interestingly none of these articles ever mentioned that they are talking only about seized currency. In this way they have done something unethical just for the sake of their shallow political gains. They have also been successful in blocking the readership of any voice which has the potential to expose their lie, since they have control over most of the academic journals and newspapers, with large circulation. By doing so they have set another example of academic intolerance.

References:

Gupta, Anish (2017). Does Counterfeit Currency Data Conceal More than It Reveals? EPW Vol. 52, Issue No. 3, 21 Jan, 2017.

Rajakumar, J Dennis and Shetty, S L (2016). Demonetisation: 1978, the Present and the Aftermath. EPW Vol. 51, Issue No. 48, 26 Nov, 2016

Editorial of EPW. What Were They Thinking? Vol. 51, Issue No. 47, 19 Nov, 2016.

Indian Express, February 3, 2017. Accessed from the following website: http://indianexpress.com/article/business/economy/demonetisation-black-money-most-deposited-rs-2-lakh-or-more-some-used-one-pan-for-20-accounts-hasmukh-adhia-4505017/

(Writer teaches Economics at University of Delhi)

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)