This final part of the two-part article explores how, when India stood at the crossroads of World Wars, revolutionaries like Hedgewar contemplated a nationwide uprising

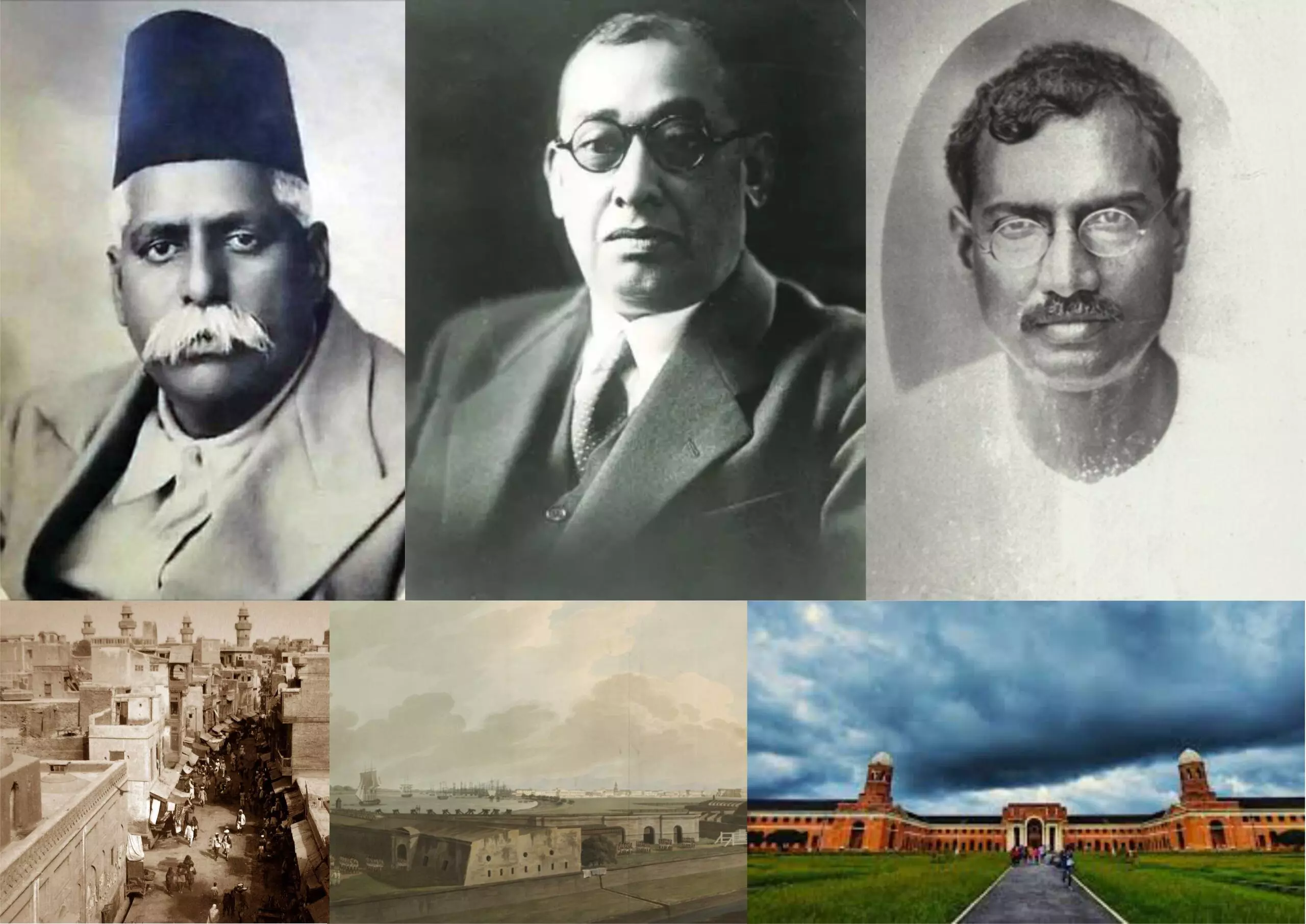

Earlier in October 1912, historian Uma Mukherjee tells us, in her opus ‘Two Great Indian Revolutionaries’, as a preparation for organising a mass uprising the decision was taken at a meeting of revolutionaries in Lahore which was presided over by Rash Behari “towards the publication of anonymous leaflets with the object of fomenting discontent in the people against the British Government.” The leaflet named Liberty was issued in May 1913, it was printed in Kapurthala and distributed throughout north India from Lahore, preaching revolution. The Liberty obviously aimed to prepare the ground for a nationwide uprising. “Revolution has never been the work of men. It is always God’s own will worked through instruments…The debt we owe to the noble spirits of the martyrs will be paid only when young men of India will begin to come forward in numbers, each to prove a worthy successor of these departed sons…A grim Revolution is the greatest need of the time. Rise, brothers, in spirit…” Words such as these were meant to galvanise the youth into action. In fact, first copies of Liberty, once out, were seen almost everywhere, in school and college premises and were, as McQuade describes it, “distributed by mail to a wide recipient from across the political spectrum.” Copies of Liberty must have most certainly reached Nagpur.

The nationwide revolt was fixed for February 21, 1915. McQuade writes, “with Lahore as the epicentre of a full-fledged rebellion comprising a series of connected uprisings in Ferozepur, Rawalpindi, Ambala, Meerut, Benares, Agra and elsewhere.” The Sedition Committee Report — better known as the Rowlatt Committee Report — of 1918, describes Rash Behari’s exploits thus, “Early in February, he arranged for a general rising on the 21st of February of which Lahore was to be the headquarters. He went there and sent out emissaries to various cantonments in Upper India to procure military aid for the appointed day. He also tried to organise a collection of gangs of villagers to take part in the rebellion. Bombs were prepared; arms were put together; flags were made ready; a declaration of war was drawn up; instruments were collected for destroying railways and telegraph wires.” The style and preparation were certainly 1857-like. It alarmed investigation agencies who uncovered the plot later, when they realised that the central focus of this revolutionary attempt was to effectuate a revolt in the Indian Army against the British.

One of the foremost historians of the pre-Gandhian phase of India’s freedom struggle, Prithwindra Mukherjee, has left behind an interesting conversation regarding the attempt to organise an 1857-type revolt taking advantage of a world war. Mukherjee’s thesis on the “Intellectual Roots of India’s Freedom Struggle (1893-1918)” remains one of the most authoritative studies of this phase. In his “Bagha Jatin – Life in Bengal and Death in Orissa (1879-1915)”, Prithwindra Mukherjee writes that Rash Behari’s contact with Jatin Mukherjee – Bagha Jatin – “added a new impulse to Rash Behari’s revolutionary zeal; in him Rash Behari discovered ‘a real leader of men.

Through Motilal Roy of Chandernagore, one of the leading ideologues of the Chandernagore group of revolutionaries, who later founded the Prabartak Sangha and with whom he was closely connected, Rash Behari had kept a channel of communication open with Sri Aurobindo, then in exile in the French enclave of Pondicherry. “Rash Behari asked him to verify with the Master [Sri Aurobindo] whether Jatin’s was the right decision to organise all over India an 1857-style of insurrection in case of a World War.” Motilal is said to have returned “from Pondicherry with full approval and blessings from Sri Aurobindo.” Rash Behari, writes Joseph McQuade, “was the first modern revolutionary to cobble together a movement that stretched across the entire expanse of northern India.”

Hedgewar’s revolutionary association, his participation as part of the attempt at effectuating a nationwide rebellion during World War One and his contemplating a similar possibility later during World War Two, must be seen, thus, against this vast canvas.

Dr Hedgewar believed, argues Rakesh Sinha, that “two factors were essential for any revolution to succeed, firstly, a committed organisation and secondly; the country’s imperialist rulers would have to be bogged in external events” that is, international political circumstances. He had not forgotten his past experiences.

Doctorji thus clearly saw another great opportunity for India to achieve freedom with the impending World War. Addressing a gathering in 1939, he referred to the possibilities of another revolt against foreign domination in order to free India. The old spark had not faded a bit, the revolutionary training and indoctrination had remained intact over these intervening decades. Displaying impatience with those who were “advocating patience in attaining freedom,” Doctorji argued that the “goal of the RSS was to attain freedom.” Sinha sheds light on this very crucial address by Doctorji. “If we don’t achieve freedom now, it will be impossible for us to gain it in the future…”, he told his listeners. For Doctorji, writes Sinha, the “crisis for imperialism was an opportunity for Indian nationalism.” He saw the circumstances as favourable as never before, “This is the time for us to work with all our heart and mind. Circumstances as fortuitous as the present opportunity didn’t appear in the past, nor are they likely to appear in future” and therefore it was imperative that all stood in readiness.

As one reads these words and of Doctorji’s own approach in 1939 and 1940, one sees a clear convergence between him and his erstwhile revolutionary colleagues from Bengal who had come to meet him and to discuss the preparedness and the possibilities of a countrywide revolt. Subhas Chandra Bose would eventually set out to join hands with Rash Behari Bose and the INA in Japan with the aim of liberating India by force through international support, taking advantage of global political circumstances. The Bengal revolutionaries, in most cases, formed an intense fraternity and the word of Doctorji’s unique organisational work which he had started in Nagpur and had gradually spread across the country had travelled and had especially reached his former revolutionary colleagues. Trailokya Nath Chakraborty’s visit and Jogesh Chatterjee’s records point to that possibility.

Source: https://www.millenniumpost.in/opinion/lost-plot-of-uprising-607636

The writer is a member of the National Executive Committee, BJP, and the Chairman of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)