A comprehensive remembrance of Bangladesh’s liberation is impossible without the recognition of Jana Sangh’s vital contribution as an opposition party

It is often forgotten, ignored or is not known that fifty years ago, the Jana Sangh – political parent or predecessor to the BJP – as one of the principal opposition parties played a crucial role in mobilising public opinion in support of recognising ‘Swadhin Bangladesh.’ Over the decades the Congress spawned an opinion and narrative constructing eco-system which created the myth of Bangladesh being a Congress alone, Congress-led, Congress directed and Congress achieved operation. This eco-system has whitewashed the contribution and participation of many other organisations, groups, individuals and collectives at various levels – social, cultural and political – which India had then witnessed in support of the ‘Muktijuddho.’

If the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War triumph was Indira Gandhi’s finest moment, the subsequent Simla pact and her complete and unexplained capitulation and surrender was also her most naive moment. That capitulation, that unthinking surrender, that incredulous clasping of Pakistan’s poison laden hand of friendship by Indira and her advisers, ensured that the Pakistan and Kashmir pot continued to be kept on the boil for the next decades with India at the receiving end. The Jana Sangh had rightly termed Indira’s irrational foray as a ‘Sell-Out in Simla.’ It spoke of being shocked at the ‘way the Prime Minister let down the country…What was won on the battlefield by the blood of the Jawans has been bartered away at the negotiating table for a piece of paper.’

The Jana Sangh’s Central Working Committee met in Delhi in 1972, argued that new uncertainties were created because of this sell-out on an issue that was long settled, that of Kashmir’s accession, and now Pakistan was acknowledged as a party to it. Moreover, issues like ‘the vacation of illegal Pak occupation of over 30,000 square miles of Jammu-Kashmir State, arms limitation, recovery of 1000 crores of long-standing dues from Pakistan as compensation for the surplus of evacuee property, including Pakistan’s share in the public debt of united India, Indian properties confiscated in 1965, and expenditure incurred on refugees pushed into India (in 1971) were not even breached by Smt Gandhi. It has been a sell-out, pure and simple’, it argued.

Bhutto had come to Simla, the Jana Sangh leadership pointed out, with three objectives: 1. Recovery of lost territory, 2. Return of prisoners of war, 3. Reopening of Kashmir issue, ‘He has won the first and third, paved the way for the second which now only awaits Pakistan’s recognition of Bangladesh.’ In hindsight most – except perhaps the beholden ‘family retainers’ – would agree with the Jana Sangh’s observation made with a certain amount of exasperation that Indira had ‘wasted a golden opportunity for a mass of verbiage’ and that ‘a victorious country should have been asked to swallow this insult by its Prime Minister, [was] perhaps the first instance of its kind in the World History.’

Instead of holding a politically motivated exhibition and function and trying to pass off the ‘Bangladesh Liberation War’ triumph as a Congress moment, the dwindling and ageing Congress Working Committee – now a pale shadow of its former self – ought to have introspected and explained the reason for its capitulation to the present generation, which seeks answers on its epic faux-pas in Simla. In 1971, what was it that India achieved in terms of securing its strategic future, what was it that India gained in terms of access to strategic routes and outlets and advantages that would have accrued with them, what was it that India gained in terms of recovering her usurped territory? All these questions ought to have been discussed by Congress and its web of opinion makers.

Returning to Jana Sangh’s activism in support of the formation of Bangladesh, it would be interesting to note a few moments. The situation in East Pakistan was fast deteriorating with the Pakistan Army carrying out a series of pre-meditated genocidal operations aiming at cleansing the Bengali intelligentsia.

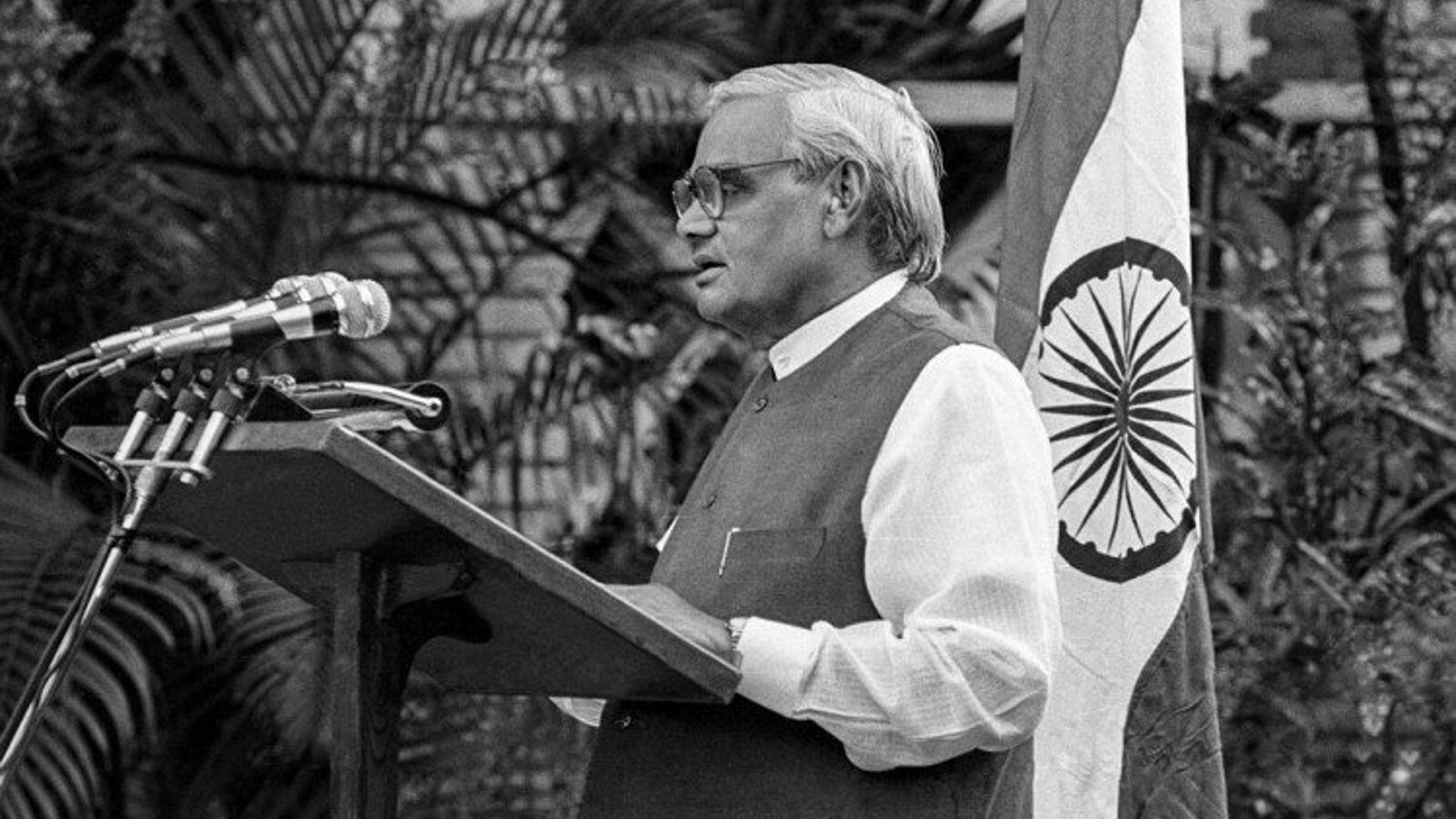

Atal Bihari Vajpayee, speaking in the Lok Sabha on June 18, 1971, in support of a resolution moved by Netaji’s political disciple, freedom fighter and Forward Bloc leader Samar Guha, who had himself left East Bengal as a refugee, in a passionate intervention described the situation in East Pakistan, ‘The political solutions about which we are talking means that the Government of elected representatives of Bangladesh should be established there, Bangladesh should cease to be a colony, the refugees who have fled could return back and their life, property and honour may remain secure.’

In an impassioned plea Vajpayee called for the Government of India to raise the issue of genocide in East Pakistan in UN, there can be only one policy for India, Vajpayee argued, that was to make a firm resolve ‘not to compromise with the present position and to create conditions in Bangladesh whereby displaced persons could return to their homes and democracy could be established there.’ For that to happen, Vajpayee told the House, ‘if there is no alternative except war India should get ready for war.

Ten days later, speaking on the ‘holocaust in Bangladesh’ and ‘liberation as the only solution’, Vajpayee movingly spoke of the need for India to go it alone, if need be and not dither, ‘if we have to go it alone, we will go ahead. Bangladesh is a country of Rabindra Nath Tagore and Kazi Nazrul Islam. Poet Rabindra had told us: ‘Ekla chalo re, Yadi tor dak sune keu na ashe, Tabe ekla chalo re’. So let us walk alone on the path of duty, go alone for the defence of democracy in Bangladesh. We are not bound to preserve the unity of Pakistan…’ In June 1971, Vajpayee was already referring to East Pakistan as ‘Bangladesh.’

In July 1971, in its all India session held in Udaipur, the Jana Sangh, speaking of rendering ‘immediate help to Bangladesh’ called on the Indira government to accord immediate recognition to the ‘democratically elected Government of Swadhin Bangladesh’ and to provide it with ‘effective moral and material help’ and to make efforts for the ‘early release Sheikh Mujibur Rehman and others under arrest.’ Referring to Pakistan as a ‘monstrous absurdity’, the Jana Sangh also demanded that ‘effective curbs be put on Sheikh Abdullah, Majlis-e-Mushawrat, Tamir-e-Millat and Jamait-e-Islam, Muslim League and other elements that have consistently refused to condemn the [Pakistan] military junta for its genocide in Bangladesh.’

In subsequent weeks and months, Jana Sangh launched countrywide political programmes in order to educate public opinion and garner public support for the recognition of Bangladesh. A look at the resolutions, debates and descriptions of these programmes, indicate the massive drive the Jana Sangh undertook in support of the formation of Bangladesh. In August 1971, it launched the Bangladesh Satyagraha month for the recognition of Bangladesh. 28,000 ‘satyagrahis’ courted arrest; among them was a young twenty years old ‘satyagrahi’, Narendra Modi, who would eventually rise to lead India as Prime Minister.

Vajpayee, Bhai Mahavir, P.Parameswaran, Sunder Singh Bhandari, Nana Deshmukh, Pitamber Das, Balraj Madhok, Bacchraj Vyas, among others, led the ‘satyagrahis’ at various places. Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Bihar, Haryana, West Bengal, Mysore, Jammu & Kashmir, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, among other states, saw large participation in the satyagraha for recognising ‘Swadhin Bangladesh.’ The Jana Sangh was unrelenting in its pressure that India recognises Bangladesh.

In November 1971, a few days before the War and the eventual recognition of Bangladesh by India, the Jana Sangh observed that ‘If India had recognised Bangladesh way back in April [1971] and given it all necessary military assistance, by now Bangladesh would have been freed from the shackles of Pakistan.’

As we observe the fiftieth year of the Bangladesh Liberation War and recall many poignant moments from the past, Jana Sangh’s role and contribution too should be recalled in order to make it a comprehensive and collective remembrance and tribute.

(The writer is a member of National Executive Committee (NEC), BJP, and the Honorary Director of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal)

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)