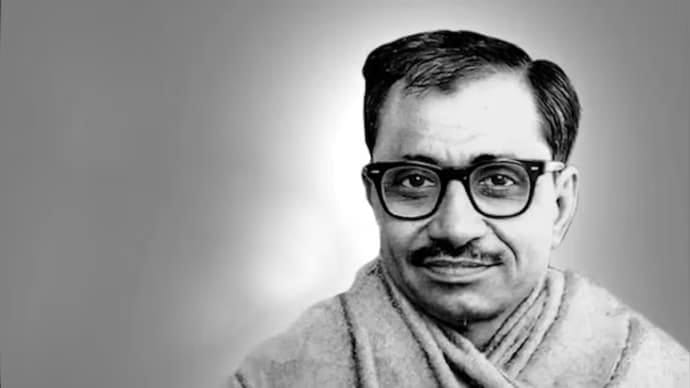

India’s quest for social justice predates the Republic, and generations of luminaries have sought to chart a roadmap for it. Like his contemporaries, Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya grappled with the issue and advocated a distinctively Indian framework. Long before “social justice” became a catch-all slogan for electoral coalitions, Upadhyaya was asking the harder question: what kind of civilisation do we wish to build once the colonial state withers away? His answer, offered through the doctrine of Integral Humanism in 1965, dismissed the sterile binaries of Left and Right and placed the weakest Indian Dalit, tribal, landless labourer at the centre of national purpose.

Integral Humanism began with the person, not the class. Upadhyaya insisted that every individual is a composite of body, mind, intellect and soul, and true development must touch each layer. This holistic lens superseded the utilitarian calculus of the then-fashionable planning models that chased tonnes of steel while leaving slums to fester. For Upadhyaya, any growth strategy that starved the spirit, ignored culture, or entrenched humiliation was unjust.

From this premise emerged Antyodaya the rise of the last person. Upadhyaya’s bottom-up moral arithmetic is unambiguous: “Daridranarayan, the poorest person, is my God. Unless the service of the poorest is complete, society cannot progress.” Serving the last hut, not the first skyscraper, therefore became the litmus test of policy. He went further, arguing that even if a person is not able to produce or earn, his primary needs should still be fulfilled. Food on the plate, medicine in the clinic, clothes on the body, roof over the head and a book in hand, these were not alms but national duties. He said, “By and large, we can see that food, clothing, shelter, education and medical attention are the five basic necessities of every individual which should be fulfilled. If we want to assess the material standard of life of any country, we could take these as a starting point. If any class of a society does not get these facilities, we may say that the standard of life of that society is not developed”.

Upadhyaya’s egalitarianism, however, refused to outsource morality to centre alone. He envisioned economic democracy a republic where the right to participate in workplace decisions is as sacred as the right to vote. Employee ownership, cooperatives, village-level credit and decentralised planning were his antidotes to both capitalist monopoly and socialist commissar rule. Such decentralisation mattered for caste justice because it punctured the economic stranglehold of hereditary elites and opened vertical mobility for Dalit entrepreneurs, artisans and farmers otherwise locked into feudal labour circuits.

Critics sometimes caricature Upadhyaya as a romantic of varṇa, yet his Integral Humanism explicitly “envisioned a society devoid of caste, class and war”. He located untouchability not in scripture but in the corrosion of Dharma a moral order that once bound diverse occupations into a cooperative organism before ossifying into birth-based tyranny. The cure, he argued, was dual: first, regenerate cultural pride so that no calling is despised; second, guarantee economic and educational opportunity so that social status no longer tracks ancestral labour. Here, Integral Humanism and the Dalit quest for dignity converge, both demanding annihilation of hierarchy, albeit through inner reform rather than class warfare.

Upadhyaya was also a critic of the state itself. He called for a “Dharma Rājya” a government for the good of the people, restrained by morality and animated by decentralised power. Reservations, targeted welfare and labour protections all fit comfortably within this canvas, but they were never meant to degenerate into transactional vote banks. Instead, the state was to be the guarantor of minimum dignity while families, temples, guilds and civic bodies nurtured fraternity. Social justice, stripped of fraternity, he warned, mutates into grievance markets.

On the ground, his touchstones were concrete. He framed the progress of any society by the advancement of the most disadvantaged segments, a principle that now animates indices from rural electrification to the saturation of bank accounts. He hammered home that education cannot be mediated through social and economic privileges; without literacy of the weaker sections, India would remain shackled. And he advocated that every hand finds work and every field finds water a slogan later crystallised as “Har haath ko kaam, har khet ko paani”.

How does this vision converse with B. R. Ambedkar, the other colossus of social emancipation? Both men insisted that the state shoulder the weakest, but where Ambedkar foregrounded legal equality, Upadhyaya foregrounded cultural cohesion. Yet the overlap is striking: each held the complete development of body, mind, wisdom and soul as the end of policy. Each called economic democracy indispensable. And each measured national greatness by the fate of the weakest of the sections of the nation. The social attitude and state policy must adapt to the most deprived’s concerns and interests. Integral Humanism is integral to the idea of fraternity, the bridge that links Ambedkar’s ethical pursuit of liberty and equality. That two intellectual traditions could converge on core priorities speaks to the tensile strength of India’s civilisation argument when purged of colonial filters.

Upadhyaya’s relevance today is greater than before. Seventy-five years after the Constitution, caste discrimination lingers in subtler guises: urban wage gaps, digital exclusion, and environmental injustice. Integral Humanism offers a conceptual toolkit to tackle these second-generation inequities. Its insistence on marrying economic growth with cultural respect pre-empts the paternalism that too often creeps into top-down welfare. It’s a call for hyper-local decision-making that aligns with the digital age’s push for platform cooperatives and self-help groups. And its moral vocabulary of Daridranarayan abolishes the charity complex by insisting the beneficiary is, in fact, the measure of our worth.

Some might argue that contemporary politics has outpaced Upadhyaya, trading his ethical rigour for electoral calculus. Yet when the government ensures public provision of private goods like gas cylinders, funds tribal hostels or seeds rural start-ups, it is paying homage knowingly or not to his design . Likewise, when the Centre’s flagship schemes build housing for the poor, free grain or micro-credit disproportionately to households historically left outside the village chowk, they echo Antyodaya more faithfully than any manifesto.

None of this obscures the unfinished business. Economic democracy remains an aspiration. Decentralisation is stymied by bureaucratic centrism. And caste prejudices sometimes re-arm themselves with new weapons of social media slander. Upadhyaya offers no silver bullets, but he does offer a compass: judge every law, budget and social norm by its impact on the man at the end of the queue. If he steps forward in dignity, we progress; if he stands frozen in shame, we regress.

In the final reckoning, Deendayal Upadhyaya rescued social justice from the ideological rigidities and political rhetoric and rooted it in the civilisational soil of Bharat. He reminded a traumatised, newly free nation that the worth of a civilisation is not in its monuments alone but in the handshake across caste lines, in the dignity accorded to labour, in the quiet confidence of a child dreaming to fulfil her aspirations. Modern India is still a work in progress. Still, its scaffolding-the moral steel of Integral Humanism-owes much to a philosopher-politician who dared to see the divine in the destitute and demanded that the Republic do the same.

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)