The rapid growth of industrialization and technological innovations in the twentieth century brought about unprecedented environmental challenges, prompting the global community to prioritize the degradation of natural ecosystems and the sustainability of human development. Recognizing the necessity for a coordinated international response, the United Nations convened the Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm in June 1972. This landmark event represented a pivotal moment in the evolution of environmental justice and governance, resulting in the adoption of the Stockholm Declaration—a foundational document consisting of 26 principles that underscored the interdependence of environmental protection, human well-being, and economic development. Among its notable outcomes was the establishment of World Environment Day, celebrated annually on June 5 to promote ecological awareness and mobilize global action. In the subsequent decades, countries have increasingly woven environmental considerations into their national policies. India’s ecological trajectory is particularly noteworthy, characterized by its evolving legal frameworks, institutional mechanisms, and grassroots initiatives in harmonizing ecological sustainability with socio-economic development.

Post the Stockholm Conference of 1972, India’s environmental governance started coming into being. As an essential participant, India had stressed the issue of equity concerning ecological responsibility, underpinning the ideologies of environment and development. In this respect, it was stressed by India at the conference that environmental policies must be sensitive to the developmental needs of the South. The conference, in the backdrop of landmark principles, established the world environment ethic, laying deep resonance with India’s stand. These included the following key principles: Principle 1 states that man has the prima facie right to freedom, equality, and adequate conditions of life in an environment of a quality that permits a life of dignity and well-being. This was followed by Principle 11, which warned against the use of environmental measures as a means of pursuing trade restrictions or other economic barriers against developing countries. Together, these principles helped anchor India’s subsequent environmental policy in the twin imperatives of ecological sustainability and socio-economic equity.

The period from 1981 to 2000 formed a very critical phase in the institutionalization of India’s environmental governance, with a strong legal and regulatory framework established over this period. The Forest Conservation Act of 1980 was one such important legislation wherein the diversion of forest land for non-forest purposes was prohibited unless the central government gave prior approval. This was followed by another law, the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act of 1981, used for the oversight and regulation of air pollution. Later, following the Bhopal Gas Tragedy, the government passed another landmark legislation, namely the Environment (Protection) Act of 1986, which conferred upon the central government immensely vast powers to take all necessary measures for protecting and improving the environment. While strengthening the environmental institutions, these legislations also paved the way for active judicial interventions, which propelled public interest litigation in the arena of environmental justice. Against the backdrop of this domestic legal regime, between 1992 and 2015, the country aligned itself more with international ecological norms and frameworks. As a party to the Montreal Protocol, India committed itself to eliminate 98% of substances harmful to the ozone layer by 2010, thus asserting its intent to comply with environmental regulations at the global level.

After the 2015 Paris Agreement, India became a key player amongst developing countries in the world climate regime. Recognizing the imperative to reckon with the ecological side of development, India pledged that its emissions intensity of GDP would be reduced by 33-35% from 2005 levels by the year 2030. This commitment was further enhanced in 2022 during the submission of updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), proposing a revised target of a 45% reduction with 50% of cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel sources by the year 2030. These targets significantly indicated policy-level shifts toward low-carbon development, along with consideration of the energy requirements of a fast-growing economy. On the other hand, severe domestic regulatory measures were brought in for some key environmental issues. The Plastic Waste Management (Amendment) Rules of 2022 banned single-use plastics that have limited utility and direct littering potential nationwide. Complementing this ban is the enforcement of the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) scheme, requiring manufacturers and brand owners to take responsibility for managing plastic packaging waste through its life cycle. These legal instruments, some of them related to ecosystem pollution, some others excluded in the beginning-intention to integrate circularity and responsibility into India’s industrial ecosystem.

The early days after 2023 saw an accelerated interest in and play in multilateral environmental discussions, especially during the G20 presidency. It was during this stint that India launched its LiFE (Lifestyle for Environment) movement to promote a shift in the behaviours linked with sustainable consumption and production practices. This campaign placed India as a climate-resilience thought leader at the microscopic and macroscopic levels of mobilization. Beyond this, global climate finance worth USD 5.8 billion stands as proof of India’s commitment to aid the developing and least-developed countries in the low-carbon transition. The International Solar Alliance (ISA) formed the foundation around which India crafted its climate diplomacy strategy during this period. With over 120 countries as members, the ISA set an ambitious target of creating more than USD 1.1 trillion in investments for solar infrastructure by 2030. The principal aims included bringing down solar technology and financing costs, as well as energy access and security in the Global South. On the clean air front at home, the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) contemplated reducing PM2.5 and PM10 levels in cities vis-à-vis the 2017 baseline by 20-30% by 2024. This set of actions paints a picture of the country holding simultaneous interests in fostering solid environmental outcomes at home and asserting its influence in shaping global environmental governance.

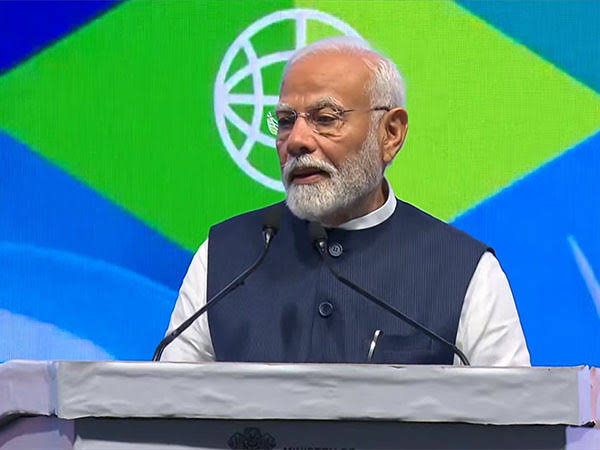

In the future, India is well placed to act as a determining force in shaping the direction of global environmental negotiations and agreements. In particular, its engagement with the negotiations on the Global Plastics Treaty exhibits a desire to export domestic best practice—specifically, the EPR model and single-use plastic prohibition—to the broader global community. This ties into India’s vision to shift from a linear model of resource utilization to a circular economy with minimal waste and retention of material value in the cycle of production. At the same time, India continues to aim for aggressive renewable energy targets. As of early 2025, the nation had installed a record 30 GW of clean energy in one fiscal year, and is on course to meet its goal of 500 GW of non-fossil fuel capacity by 2030. With around 170 GW of renewable energy schemes already in the pipeline, India is solidifying its position as an international renewable energy hub. In a symbolic reiteration of its green cradle policy, Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the Aravalli Green Wall Project on World Environment Day, 5th June 2025. The massive reforestation project will revive the 700-km-long chain of Aravalli mountains stretching across Delhi, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Gujarat. The project will not only increase forest cover and biodiversity but also serve as a natural defense against desertification in northwestern India. India’s changing environmental strategy is a consistent and multi-dimensional approach, grounded in policy creativity, global partnership, and environmental renewal. Entering a new era of sustainability leadership, India’s actions increasingly embody the synthesis of ecological integrity and socio-economic resilience, which serves as a model for other emerging economies globally.

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)