By Blessy Mathew Prasad

- CHENNAI:There could probably be no disagreement on the fact that education shapes minds and ideologies. But with all the recent demands for the ‘Indianisation’ of education, the question really is ‘what does Indianisation’mean’? Should students be denied the chance to understand their history, conflicts that arose, and foundations of modern India?

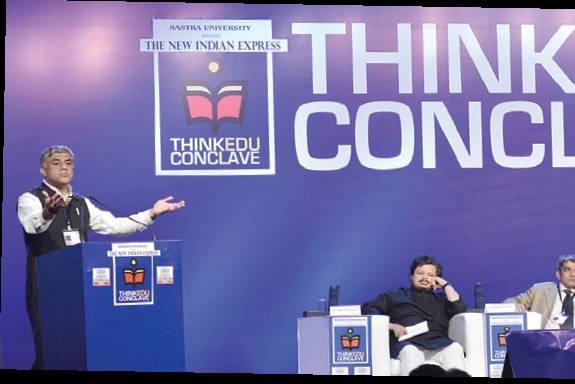

“There are problems in the foundations on which you build future, what are those foundations, how did we get there, was there exploitation, injustice and violence in the past, how was it perpetrated and how was it justified. All those questions need to be answered before you can move forward. At the same time, we should also make sure that you don’t get caught up in some divisive story about something that happened thousands of years ago. You have to focus on how to make education come alive in such a manner that people can relate to the world in which they live,” says Rajeev Gowda, MP.

He adds, “Too often, because our higher education has not been Indianised enough, we haven’t got enough of an understanding of our context, and conflicts. If we talk about urban planning today and don’t understand that villages were built in segregated ways, that some communities had issues about not getting enough access to facilities, all that is necessary to build newer cities. So there is a need for some amount of historical knowledge.”

Anirban Ganguly, Director, Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, says the problem is not when there are too many different ideas, but when one idea continues to dominate and leaves no room for other ideas to develop.

He says, “The problem is when one idea of India dominates and practises academic apartheid. And when that idea is no longer dominant, it accuses others of being intolerant.” He went on to say that we cannot practise academic apartheid for decades and not allow a certain conception of India to come out and it is academic apartheid that makes for a selective reading of thinkers. Ganguly proposed setting up of centres where we study the history of the communist party in India and thinkers like Dr Syama Prasad.” Chair Shankkar Aiyar ended the session with the concluding remark that “You can interrogate history, but you cannot prosecute it.”