By Mukesh Kumar Srivastava

This book gives a very readable micro-analysis of many of the important schemes introduced by the Modi Government in the past few years. But it leaves out some others

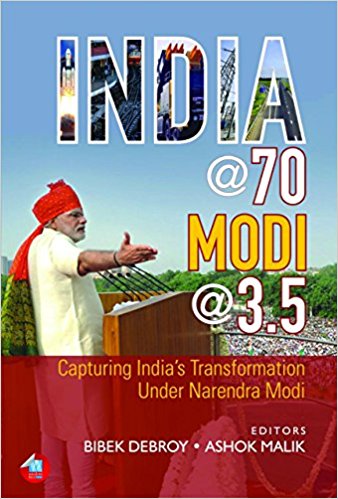

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi completed three and a half years in the government, there has been much contemplation and deliberation on the achievements of his Government in terms of foreign policy and socio-economic reforms. The book India @ 70, Modi @ 3.5: Capturing India’s Transformation under Narendra Modi, which is under review, attempts to provide answers to such debate.

The first three chapters dwell on the philosophical, political and socio-economic underpinnings of governance under the Modi government. Through an analysis of speeches and statements made by Prime Minister Modi on different occasions and platforms, author Anirban Ganguly introduces the basic philosophical essence of “Narendra Modi’s Transformative Philosophy of Governance” — an integral part of ‘Modi Doctrine’. With candid explication of excerpts and initiatives, the author describes the main elements of PM Modi as embedded in Jan-Shakti, Jan Bhaagidari, Samvad, and Yuva-Shakti. Simply put, it means citizens’ participation as the ‘agents of change’ to ‘bring about an alteration of mindset of those in power and towards power.’ (p. 3). The most significant and conspicuous instance of Jan-Shakti and Jan Bhaagidari, cited by the author, is the support that the policy on demonetisation received despite drawing criticisms from different quarters. In his view, PM Modi stresses on bringing synergy among the various parts of governance — political class, civil servants and the people — to ‘reform, perform and transform’ (p.5). In building a “New India”, particular focus is given on harnessing the ‘great demographic dividend’ (p.6). Chapters 2 and 3 discuss the incremental changes brought by the present government in the socio-economic realm. Swapan Dasgupta observes that ‘there was visible significant shift in priorities and approach’ (p. 13). He adds that the government has stressed on improving investment climate as well as domestic capacities, and expanding its social base aimed at poorer sections of the population through initiatives like Ease of Doing Business, Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT), Jan Dhan Yojana, Swachh Bharat and BHIM. In ‘Minimum Government, Maximum Governance’, Debroy explicates initiatives — Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY) and DBT — that facilitate citizens’ participation.

The next three chapters focus on tax reform and LPG programmes in India. Arvind Virmani argues that while GST has been successfully implemented, there remain certain challenges to be addressed. Recognising the difficulties in removing subsidies, authors Kirk R. Smith and Hindol Sengupta, discuss the cost and the scale of implication in providing LPG through initiatives like Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY), while linking it to DBT. The next seven chapters analyse health and social protection schemes as well as policies at urbanisation, connectivity, water and energy security. The chapters argue that the government has taken into cognizance that there is an intrinsic link not only between economic, water and energy security, but also connectivity and urbanisation. Uttam Kumar Sinha says that ‘water security is a critical enabler to economic growth’ (p.109). Government initiatives like International Solar Alliance (ISA), Namami Gange and Sagaramala, alongside health security schemes like the National Health Protection Scheme, discussed in the seven chapters, are aimed at bringing synergies in different sectors for integrated and sustainable development. The other schemes targeting different groups of people in terms of health and social security include Atal Pension Yojana (APY), Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana (PMSBY), ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’, Skill India, Make in India, Startup India, Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gram Jyoti Yojana (DDUGJY), Smart Cities, Swachh Bharat Abhiyan and such others.

The fifteenth and the eighteenth chapters portray the balanced mix of hard and soft-power elements of Modi’s foreign policy. By focusing on defence procurement and modernisation, author Nitin A. Gokhale illuminates on the ‘new sense of vigour and purpose in the largely moribund MoD’ (p. 162) infused during Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar stint. By referring to Kautilya’s Arthashatra, Veena Sikri elucidates the soft-power discourse of Modi’s foreign policy based on Panchamrit — samman (dignity and honour); samvad (greater engagement and dialogue); samriddhi (shared prosperity); suraksha (regional and global security); and sanskriti evam sabhyata (cultural and civilisational linkages) (p.184).

Promotion of soft-power through culture and civilisation has been a sine qua non of PM Modi’s visit to various countries and his espousal of International Day of Yoga. Chapters sixteenth and seventeenth discuss Modi’s foreign policy towards South-east Asia and China. Expounding the conduct of relations with South East Asian region through Act East Policy, PM Heblikar draws to light the significance of the region in Modi’s foreign policy. He identifies many common areas of interest where cooperation is possible between India and the region, including defence procurement, demining, disaster management, terrorism, etc. Similarly, Jayadeva Ranade evaluates PM Modi’s policy positions towards China, citing references to issues ranging from People’s Liberation Army (PLA) intrusion at Chumar in Ladakh to that of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) and terrorism. He observes lucidly Modi’s ‘new policy of firmly raising issues of concern with China’, particularly in the wake of its growing assertiveness. (p.180) The book endeavors to offer a balanced perspective to the reader by answering the questions pertaining to the working of the Modi government as well as highlights the gaps that need to be filled in some of the sectors for transforming India. However, the editors’ note underlines, “…while there is broad appreciation, as it to be expected, writers make subjective calls on where they see shortcomings and scope for improvement…” (p. xi). One of the limitations of the book, and as candidly expressed by the editors, is that the collection of essays discussed some sectors in an elaborate way while leaving other important sectors. Hence, the book falls short of providing a full picture of the working of the Modi government. Indeed, the readers will have to wait for the ‘sequel’ to this book, as indicated by the editors, for a holistic picture. Nonetheless, the novelty of the book lies in its micro-level analysis, delving into specific schemes undertaken by the government. Also, it delves deeper into the realm of nation-building, positing the Modi government and its contribution to the same. It is a good read for both scholars and practitioners who have questions regarding the accomplishments of the Modi government.

(The reviewer is a Programme Assistant at ICCR, New Delhi)