By Gautam Mukherjee

The collection of essays on the functioning of the Modi Government in the past 3.5 years is refreshing in both its tone as well as analysis

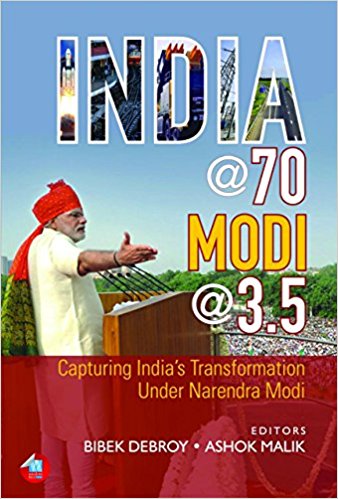

This book was released by Finance Minister Arun Jaitley at the Nehru Memorial Auditorium amongst functions to commemorate the 3.5 year mark of the Modi Government. That the next day’s headlines spoke of a former occupant of his high office applying for a job “at eighty”, was based on an incidental quip from Jaitley, and no fault whatsoever of this worthy collection. It has 18 essays written by that relatively rare breed of intellectuals from the right-of-centre, in a field generally crowded with ideological Leftists, and not just in India. It includes amongst its line-up, think-tank functionaries, journalists, bureaucrats, diplomats, and other Government officials.

The tone of the book is confident and upbeat throughout. But perhaps Prime Minister Modi put the emergence of the BJP best. It is now at centre-stage with an electoral majority for the first time in its history, and also after 30 years nationally. He did so, in another context, that of Indo-American relations, by saying India was ready to get over “the hesitations of history”. Swapan Dasgupta, now a Rajya Sabha MP, points out that the Modi-led BJP has set about expanding its political base as of 2015. This is borne out by the increase in vote shares creeping up towards 40% on average, and in isolated cases, even higher than 50%, at subsequent Assembly elections.

The engineering of it saw a new emphasis on providing succour to the rural and urban poor, and the lower middle classes. This was combined with unprecedented public spending on infrastructure in the absence of much initiative from the debt-ridden private sector. This increase in vote share, evident post demonetization, but before the advent of GST, is seen in the clutch of five states that went to the polls along with Uttar Pradesh.

It can well be contrasted with the share of the principal Opposition Congress declining from some 28% at the last General Elections in 2014 (to BJP’s 31%), languishing, in some instances, into disastrous single-digits. And Dasgupta also makes the telling point that Modi’s new politics, ( ably aided by chief election strategist and Party President Amit Shah), shows no compunction in hopping back and forth across the Right-Left divide. He is something of a city expert from his earlier experience in Singapore, and makes the point that India will soon become an urban majority country “within a generation”. This is, of course, the glide path of emerging economies growing into developed ones. It is however a long way from MK Gandhi’s “India lives in its villages”. But the challenges of managing an influx to total a billion city folk will be considerable. Sanyal suggests that India will have to considerably pick up its game on “Urban Management”. He sees urban poverty not as static but a “dynamic flow”, and says all countries which are now much better developed had tremendous slums in the urbanization phase. This includes London and New York.

He suggests facilitating the rural to urban migration process, and encouraging the dynamism that slums with “shops, mini-factories, people moving in and out,” typify, at once bringing up visions of the Dharavi Slums in Mumbai, amongst the biggest in Asia. This means, keeping the organism alive and thriving through the transition, and much more than providing a roof over the migrant’s head with “low-cost housing”. The essays on Health, Water, Sustainable Development, Tax Reform, while well laid out and argued, leave one less enthused, because most members of the general public can’t see any improvements visible on the ground. Ditto the much-publicized flop of the Swachh Bharat Mission, against a rising tide of filth, sewage, garbage and pollution. And the less said about the “Minimum Government Maximum Governance” slogan, probably the better. The Ministry of Defence remains a Tower of Babel where things are forever expected to happen but don’t. The chapter on ASEAN and South East Asia by PM Heblikar is interesting because of the 11 heads of Government from the region slated to grace our Republic Day parade in January 2018. This, soon after Modi’s own visit to meet all of them at the Manila Summit recently. India’s attitude to South East Asia has been ambivalent and luke-warm for too long, despite policy professions of “Act East”. The efforts being made now for a better political and economic engagement with the region promise to yield good dividends.

Anirban Ganguly of SPMRF flags Modi’s desire to create a “New India”, a self-renewal, driven by: “ innovation, hard-work and creativity”. Diplomat Veena Sikri highlights the remarkable rise in India’s “soft power” under Modi’s determined engagement with the countries of the world, some visited by an Indian Prime Minister after decades, some for the very first time. Recent opinion polls show that the masses of India as well as the urban elite still repose great faith in Modi’s leadership, at a time when the “honeymoon period” is long over. And this by itself is the main message at the end of more than 3.5 years of the Modi Government.

(The reviewer is an entrepreneur and former corporate executive)