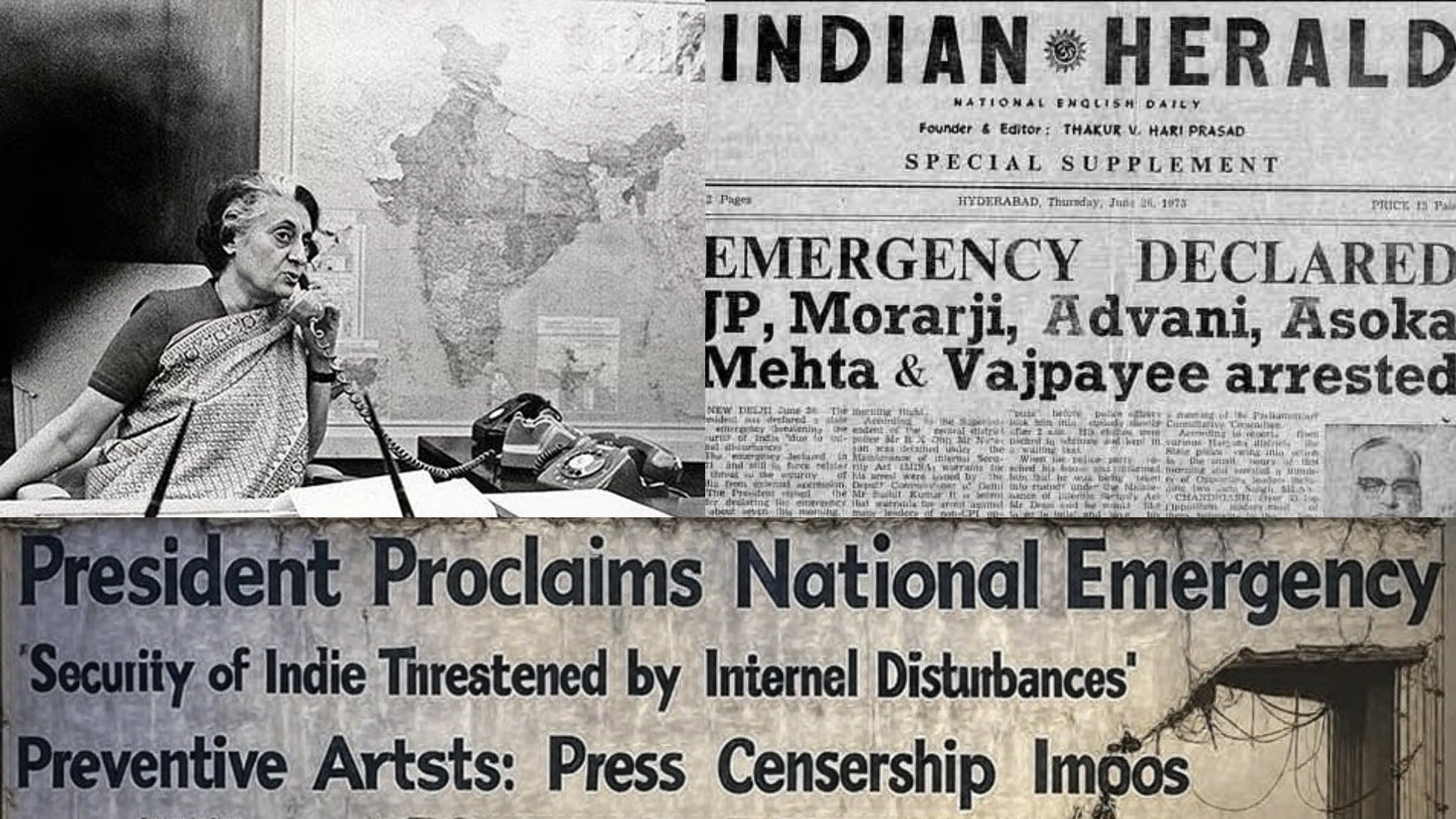

On the night of June 25, 1975, India changed forever. The then Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, declared a state of Emergency, citing threats to national security. In truth, what followed was one of the darkest chapters in independent India’s history—an unprecedented assault on democracy, civil liberties, and, most notably, the freedom of the press. For 21 months, the world’s largest democracy functioned without its most basic democratic rights. Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution—guaranteeing freedom of speech and expression—was effectively suspended. Censorship was imposed on newspapers, journals, radio, and literature. The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting issued strict instructions: news was to be vetted, rewritten, or entirely blocked if it deviated from the government’s official narrative.

The result was chilling. Major newspapers became tools of propaganda, their headlines reduced to state-approved slogans. Publishing houses lost power overnight. Book manuscripts were confiscated before printing. Opposition leaders, writers, poets, and actors who dared to question the regime were arrested or silenced. Fear and conformity replaced debate and dissent. According to Freedom House, India’s global press freedom ranking, which had been as high as 3rd in the early 1970s, plummeted to 34th during the Emergency. The New York Times called it a “devastating blow to democratic society.”

The numbers speak for themselves. In the first year alone, nearly 9,876 journalists were jailed. Over 2,974 cases were registered against individuals and groups for publishing or distributing “clandestine literature.” Among them was Kuldeep Nayar, editor of The Indian Express, who was imprisoned for his open resistance. Other prominent voices—like K.R. Malkani, editor of the RSS-affiliated Motherland, and Lala Jagat Narayan, head of Hind Samachar—spent the entire Emergency behind bars. In his book The Midnight Knock, Malkani recounts how Motherland was the only newspaper to publish the truth on June 26, 1975—informing citizens not only about the Emergency but also about the wave of arrests and protests across the nation. The cost of truth was high. The newspaper’s office in New Delhi was cut off from electricity, while its neighbouring left-aligned paper, Janayug, continued operating without hindrance. This was not governance; this was targeted repression.

Adding to the media crackdown, Indira Gandhi formally articulated media policies, accusing newspapers of “inciting violence and instability.” This framing was used to justify harsh censorship across the board. As a result, several independent publications were forced to shut down due to pressure, lack of access to printing, or financial strangulation. Simultaneously, All India Radio (AIR) and Doordarshan—India’s primary electronic media platforms—were instructed to function solely as instruments of government propaganda, broadcasting content that mirrored the ruling party’s version of the truth.

Beyond the structural damage to press and politics, the Emergency also inflicted deep personal wounds. One of the most heart-wrenching accounts comes from Defence Minister Shri Rajnath Singh, who was then a young political worker. He broke down publicly while recalling how, during his imprisonment, he was not allowed to attend his mother’s last rites. His grief symbolizes the pain endured not just by leaders but by countless ordinary citizens whose basic human dignity was denied during this dark period. Ironically, it was Indira Gandhi herself who had once proposed making All India Radio autonomous when she served as Information and Broadcasting Minister in 1966. But as Prime Minister, she reversed her own vision. Instead, 140 hand-picked loyalists were placed in AIR.

During the Emergency, more than 171 of her addresses were broadcast on AIR and Doordarshan, while opposition voices were deliberately blacked out. The public broadcaster was turned into a megaphone for one voice, one agenda. Post-Emergency, the Shah Commission, set up to investigate the abuses of that period, exposed the full extent of censorship and coercion. It found that authentic information was suppressed, public opinion manipulated, and intellectual dissent forcibly crushed. The long-term consequences were not just political—they were psychological. Citizens had learned to fear their own thoughts.

Today, as debates around media regulation resurface, especially in the context of election manifestos and policy proposals, it is crucial to remember this history. Critics have already raised concerns over the 2024 Congress manifesto, which some believe contains measures that could once again tighten control over the media—a domain that has consistently exposed malpractice, corruption, and ideological appeasement.

The Emergency was not just a constitutional crisis. It was a warning to future generations—a reminder that even a vibrant democracy like India can fall silent when checks and balances collapse and press freedom is traded for political survival. As we reflect on that era, the message is clear: a free and independent press is not a luxury—it is the lifeline of democracy. To lose it, even briefly, is to lose the soul.

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)