In 1962, Pandit Nehru continued his passive response to blatant signs of aggression by the Chinese, preferring to appease and parley with the enemy

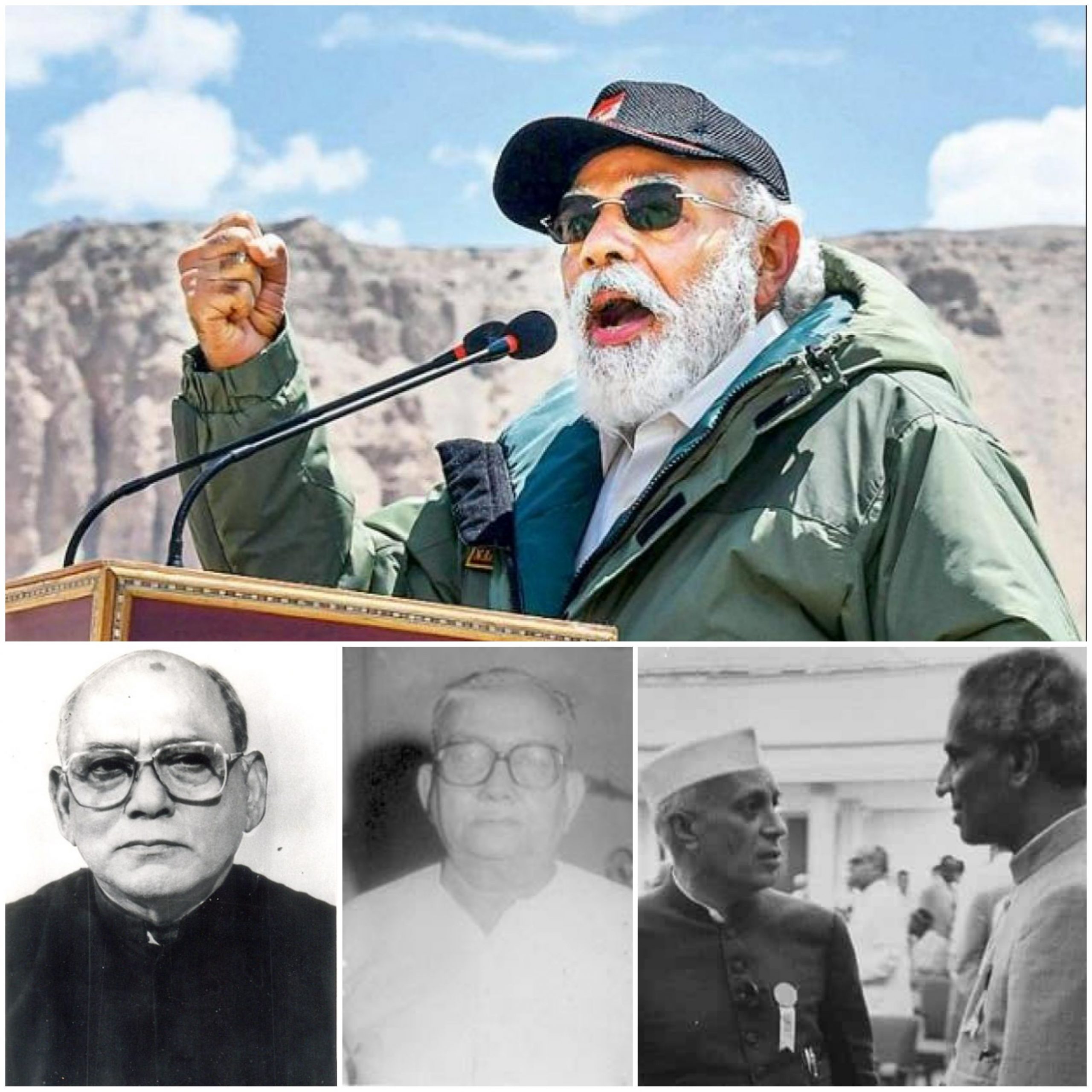

In the first week of July this year, six strategic bridges near the international border and the Line of Control with Pakistan in Jammu and Kashmir were inaugurated. India’s drive for enhancing and strengthening her border infrastructure and defence continues unabated. Since 2014, when he became Prime Minister, Narendra Modi has displayed consistent determination to ensure that the construction of India’s border infrastructure sees a quantum leap. While Rahul Gandhi keeps trying to cover-up on the failures of his family and ancestors, Modi works for empowering India. Let us continue our discussion on 1962 since Rahul Gandhi has expressed his desire to make “current affairs, history and crisis clear and accessible”, whatever that means, let us continue with making the history of 1962 accessible to the general reader.

On August 13, 1962, Lok Sabha saw a major debate on the ‘India-China Border Situation’, Nehru told the House that on July 27, there were three instances of firing by the Chinese troops from a distance, “in the Pangong lake area, when two shots were apparently fired towards our forces; on July 29 also in the Pangong lake area, three shots were fired.” On August 4, “northeast of Daulat Beg Oldi, one shot was fired…We have protested to the Chinese Government about the first two incidents.” Chinese adventurism in the Galwan area is not new, but in his days Rahul Gandhi’s great grandfather only mouthed ‘protests’ against it. The problem with Nehru was that he was never categorical on India’s position or stand when it came to China’s repeated attempt to grab and prey on Indian Territory. This had been his consistent policy and had especially accentuated when China had built the highway across Aksai Chin. By 1962 August to expect that Nehru would effectuate a course correction, was being fanciful.

The August 13, 1962 debate which discussed the India-China border situation is an important debate. Two parliamentarians from Odisha, one an erstwhile ruler of a princely state — a king — and the other a socialist, took Nehru’s China policy to the cleaners. Surendranath Dwivedy, a leading socialist voice, intellectual and activist, Praja Socialist Party (PSP) member of Parliament from Kendrapara and Pratap Kesari Deo, the last ruler of Kalahandi state, then Swatantra Party member of Parliament from Kalahandi, both tore down Nehru’s and his Defence Minister, the prone to hectoring Krishna Menon’s actions. Both Deo and Dwivedy exuded a deep mastery of the issue, radiated robust patriotism as well as strategic pragmatism.

Dwivedy pointed out that Nehru’s approach to the issue over the years has created a “suspicion” and “feeling” among the minds of the people that “we are going in for appeasement”, the minimum that needed to be done was to proactively prepare to defend one’s territory and frontier, “I do not think that to defend one’s frontier or territory or to prepare to protect it can be called a war-like activity.” Dwivedy then went on to expose Nehru’s policy of kowtowing to the Chinese even at a time when they had been firing on our soldiers and by Nehru’s own admission the situation was serious. In the midst of the firing, Nehru had dispatched Krishna Menon to talk to the Chinese in Geneva. It was an unthinkable act of letting down the entire nation. “I cannot for a moment imagine”, Dwivedy confronted Nehru, “how a Defence Minister…when our men are in a most difficult position, when our country is threatened, when the whole country is surcharged with emotion, could go and talk with the Foreign Minister of an unfriendly country?”

What was even more damaging was that in Geneva, after his meeting with the Chinese Foreign Minister, Menon, once again parroted, with flourish in public, his and Nehru’s favourite line, in which he again referred to the Indian areas that China was eyeing as “largely unoccupied areas.” “Here is a call given by the Prime Minister to be wide awake because a serious situation has arisen”, argued Dwivedy, “and there comes the explanation from the Defence Minister, from Geneva, that these are largely unoccupied areas.”

Dwivedy also referred to Menon’s response to the Indian press which confronted him on his return. Menon’s reply, in trying to brush away his deliberate and calculated faux-pas was typical of the man himself, arrogant, abrasive and vainglorious, “I am not going to explain matters to you because the pressmen are always misreporting me. If I say that I have eaten the banana you will report that a banana has eaten me.” Dwivedy was at his derisive best when retorting to Menon’s cavalier dismissal, “I am surprised that he is always misreported, misquoted in the Indian Press. In the Parliament, he is misunderstood, and in the western world, he is misunderstood. Perhaps, the only people who understand him better are the Chinese…” The issue, Dwivedy reminded Nehru, was “keeping and maintaining the integrity of the nation, which has won independence after a hard battle.”

PK Deo’s intervention was equally devastating. Terming Nehru’s China policy as a matter of utter failure, Deo called it a policy of “complacency and a policy of appeasement in dealing with a hostile, belligerent and expansionist neighbour.” Making a detailed delineation of China’s history of reneging and of back-manoeuvring against India over the last few years, Deo argued that India’s “feeble protests” to China’s repeated acts of aggression have only “acted as appetisers to increase the appetite of Chinese territorial claims.” Deo also indicated how while Nehru merely protested, the Chinese by a “persistent emphasis of status quo” have been trying to convert their illegal possession of Aksai Chin “into a legal occupation.”

While our posts were being fired upon in Galwan and Pangong area, while the Prime Minister says it is a serious situation, Deo peaked, ready to fire the final salvo, “to add insult to injury, the photograph of the Defence Minister clinking glasses with Marshal Chen Yi [then Foreign Minister of China] and toasting ‘Hindi-Chini-bhai-bhai’ has been flashed throughout the country. It has synchronised with the clang of metals in that high altitude, the raining of Chinese machine gun fire and mortar attacks upon Indian soldiers…”

When our soldiers were making the supreme sacrifice, Rahul Gandhi’s great grandfather had directed Krishna Menon, his closest political acolyte to “clink his glass” with the adversary, as Deo blasted Nehru, “when they [our soldiers] are making the supreme sacrifice, the Defence Minister goes and clinks his glass with the Chinese Marshal whose hand has been tainted with Indian blood!”

Clinking of glass with the adversary is thus clearly an old Nehruvian habit. In 2017, when he was clinking his soup bowl with the Chinese ambassador in Delhi, at the height of the Doklam episode, Rahul Gandhi was merely perpetuating that ‘precious’ family tradition.

Pratap Kesari Deo that August morning in 1962, was speaking for many when he reminded Nehru, how for the last so many years many of them had been repeatedly saying that “China can only understand the language of determination” and yet how their exhortations were ignored. Nehru’s only policy and effort then was to generate meek protestations and when the aggressor bared its fangs, he jumped to clink glasses. On the other hand, Modi not only speaks a determined language but he also exudes determined action and determined planning, after-all for him every inch of India is sacrosanct and pulsating.

(The writer is the Director of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal)

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)