In a recent political flashpoint from Kerala, Governor Rajendra Arlekar’s act of paying floral tribute to an image of Bharat Mata triggered a storm of objections. The Chief Minister’s notification restricting Raj Bhavan’s display to “official national symbols” branded this homage as “unconstitutional.” This assertion, however, is not only legally indefensible but also culturally myopic and politically expedient.

Even more troubling is the fact that this flawed interpretation is now endorsed by some seasoned officers such as Shri P.D.T. Achary. When senior legal minds bend jurisprudence to align with political narratives, it not only confuses the citizenry but also undermines both constitutional values and national unity.

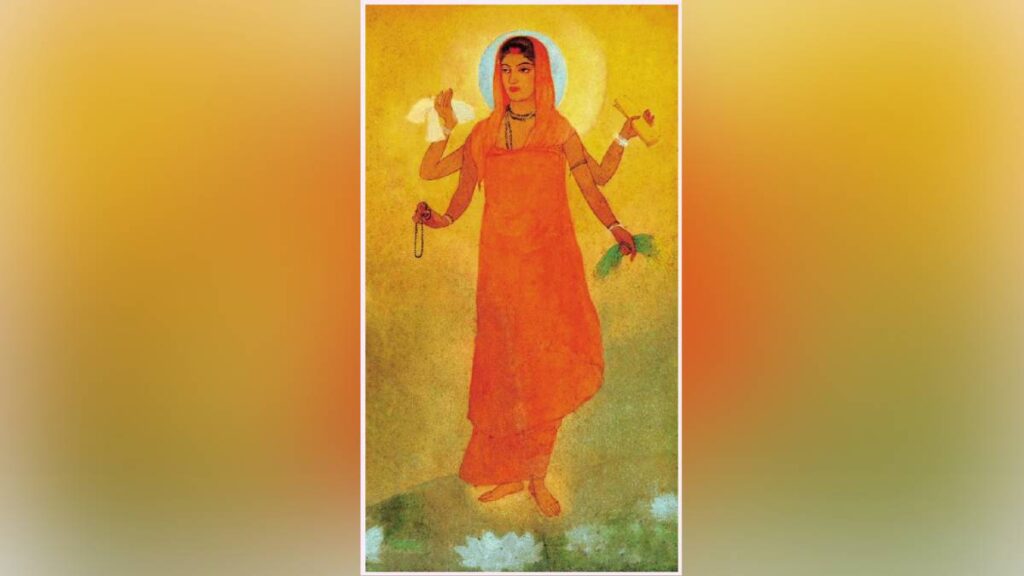

Ironically, this entire controversy arises from a state that proudly markets itself as “God’s Own Country.” Yet, its own establishment now decries the invocation of ‘Bharat Mata’, a civilisational and historical figure rooted deeply in the freedom struggle and spiritual consciousness of India. The symbol of Bharat Mata is no recent invention, nor is it a partisan emblem. It predates modern political parties, with its origins in Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s Vande Mataram and Abanindranath Tagore’s 1905 painting. It emerged as a poetic and spiritual personification of the motherland.

To reduce this timeless image to a communal or political provocation is both historically dishonest and intellectually irresponsible. Crucially, there is no constitutional or statutory bar on displaying such culturally significant symbols. The State Emblem of India (Prohibition of Improper Use) Act, 2005; governs the misuse of the national emblem but does not prohibit symbolic or poetic representations of the nation, such as Bharat Mata. The assertion that her image violates constitutional norms is devoid of any legal basis.

The principle of secularism, as enshrined in the Indian Constitution, mandates the State to maintain neutrality in matters of religion and to ensure that no citizen is discriminated against on religious grounds. However, secularism does not require the State, or its constitutional authorities like the Governor, to reject or suppress symbols that evoke national unity and cultural cohesion. In S.R. Bommai v. Union of India, (1994) 3 SCC 1, the Supreme Court held that secularism is a positive concept of equal treatment of all religions and not mere ‘non-involvement’. The Court further observed that “religion and culture are not mutually exclusive in the Indian context” and that the State can recognize and support cultural expressions that strengthen national integration. Similarly, in M. Ismail Faruqui v. Union of India, (1994) 6 SCC 360, the Court clarified that secularism in India does not require the State to be anti-religious or to erase the nation’s civilisational identity. In fact, the Court emphasized that cultural heritage is not inconsistent with secularism, and that the State may recognize symbols and practices rooted in Indian civilisational identity. Further, in Bijoe Emmanuel v. State of Kerala, (1986) 3 SCC 615, the Supreme Court upheld the right of individuals to express their reverence for the nation in forms consistent with their conscience, reinforcing the idea that patriotic expression need not conform to a single, state-prescribed format. Symbols like Bharat Mata, which transcend any single faith and represent the emotional and spiritual unity of the people, fall within the domain of cultural nationalism, not religious partisanship. Therefore, the Governor’s homage to Bharat Mata cannot be viewed as a breach of secularism; rather, it exemplifies a legitimate cultural expression that unites rather than divides.

Even historically, the Indian tradition has recognised this plural and inclusive view of governance. As Justice Rama Jois famously articulated, “Secularism in Bharat, in the sense of equal treatment for all, was part of Rajadharma, our ancient constitutional law.” Quoting from Manu Smriti (X-311): “Just as the mother earth gives equal support to all living beings, a king (State) should give support to all without any discrimination.”

And from Narada Smriti via Dharmakosha: “The king should afford protection to associations of believers of the Vedas (Naigamas) as also of disbelievers (Pashandis) and others in the same manner in which he is obliged to protect his fort and territory.” These verses prove that the inclusive pluralism of Indian secularism has deep cultural and legal roots. Yet ironically, in present times, those who invoke dharma are often mislabelled as communal.

The Governor, under Article 163 of the Constitution, is only bound to act on the advice of the Council of Ministers in matters requiring executive decisions. Ceremonial functions and symbolic expressions, such as floral tributes, fall outside this scope. To demand ideological conformity from a Governor even in such matters is to fundamentally misunderstand the office and its constitutional independence.

The real threat here is the politicisation of symbols of national unity. The act of ministers walking out from the Governor’s event—not over a policy disagreement but over a symbolic homage—marks a grave departure from constitutional decorum. Article 153 makes the Governor, constitutional head of the state. Ministers, by virtue of their oath under Schedule III, are duty-bound to uphold the Constitution without fear or favour. Their walkout reflects an abdication of that solemn duty and erodes public trust in constitutional governance.

Such hostility toward central representatives is not new. In Tamil Nadu, Governors have faced procedural disruption; in West Bengal, confrontation with the State Executive has become routine. What we are witnessing is not healthy federalism, but partisan defiance of national institutions, cloaked in constitutional language.

Worse still, this politicisation fosters dangerous binaries: those who revere Bharat Mata are dubbed “saffron,” and those who oppose are projected as “progressive.” These narratives alienate students and young citizens, encouraging them to see patriotism through ideological filters. This not only fractures civic unity but severs the emotional and spiritual connection to national identity—something that has always been interwoven with cultural symbolism in India.

The Hon’ble Governor’s stand is not only constitutionally sound but also rooted in historical and cultural clarity. The Parliament, which the Lok Sabha represents, was envisioned as a forum for the free flow of diverse ideas and ideals, not ideological censorship, to which PDT Achary belongs. The Governor rightly reminded the Chief Minister that when the Constituent Assembly adopted Vande Mataram as the National Song on January 24, 1950, the personification of the nation as Bharat Mata or Bharathamba received implicit constitutional recognition. This idea of Mother India predates Independence and resonates in the collective consciousness of every Indian.

Instead of questioning the Governor’s symbolic homage, the real debate should be: why can’t a constitutional authority pay floral tribute to Bharat Mata? Are we functioning under a living Constitution that embraces Indian civilisational ethos, or under a rigid, borrowed dogma that suppresses our cultural self-expression? It is high time we confront and reject this imported, Vatican/European model of secularism that seeks to delegitimise indigenous symbols of national unity. If India is to rise to her full civilisational and national glory, such intellectual roadblocks must be called out firmly and without hesitation.

One must also reflect on how the same ideological school once opposed Vande Mataram from being adopted as the national anthem. Only a sanitized fraction of Bankim Chandra’s original was accepted—just to appease a narrow segment. Such appeasement-driven dilution of national symbols endangers our pluralistic nationalism.

Let it be remembered: Bharat Mata is not a religious figure. She is a metaphor, a poetic embodiment of the land and its soul—shared by Hindus, Muslims, Christians, and all communities. Faith may be personal, but reverence for the motherland transcends sectarian lines. Her invocation is not an act of exclusion, but a reaffirmation of belongingness.

The Constitution begins with “We, the People of India.” That collective identity must rise above political compulsions and ideological rigidity. In defending the Governor’s cultural homage, we are not defending one party or person—we are defending the emotional and constitutional architecture of the Republic itself.

Let us stop using secularism as a political weapon to dismantle civilisational memory. Let us reclaim our right to cultural expression without fear of labels. And let us remember that the soul of India—like Bharat Mata herself—is timeless, inclusive, and indivisible.

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)