For a country of India’s size, and the challenges that it perpetually faces, having a pragmatic energy security architecture has always been of paramount importance. Since independence, as India meandered through difficult times from being an impoverished economy, almost being on the brink of a financial collapse in early nineties, and then eventually emerging, in a mere thirty years’ time, as the fifth largest economy of the world, one thing that has perpetually bothered the policymakers of India, has been the domestic impact of volatility in the global energy markets, considering the disproportionately high level of dependence India traditionally have had on imports of its energy requirements, especially crude oil and gas.

In 2014, when Prime Minister Modi came to power with a thumping majority, much like in many other sectors, which were facing systemic problems and policy paralysis, and were looking for solutions from the new regime, the energy sector too had a myriad of problems, and was hoping for a rescue mission.

The Paradigm Shift Since 2014

Much like in for other sectors, India needed a paradigm shift in thinking, and a new policy perspective to steer its energy sector, which still lacked a vision. India needed a new approach which would focus more on maintaining sectoral and institutional integrity for long term development of India, rather than continuing with populism for the sake of short-term vote gains. This was when Modi Government arrived.

Among many lobbies that worked against India’s long-term interest, one of the prime ones, was the lobby that worked to reduce India’s coal usage. There was this constant pressure from the Western countries to shun coal, even when for a country of India’s proportion and population, shunning coal at one go was always going to create a multitude of problems, given the dependence that India had on thermal energy, and given the cost of procuring alternate fuel from international market.

Not the least was how ‘environmental concern’ was fast becoming a ‘preferred barrier’ for lobbies to impede India’s developmental paradigm against which successive governments were found to be succumbing, and that resulted in innumerable key industrial projects in the past being abandoned, shelved or delayed.

For Modi Govt, The Task Was Cut Out

For Modi Government, if on one hand the challenge was to rationalise the issues of energy pricing and incentivise investments in the energy sector, the other was invariably to make sure that the seeds are sown for India’s journey towards a major economy. That needed energy stability based on a pragmatic energy policy, and energy diplomacy of a new dimension. It was critical for Modi Government from the very onset to make sure that energy and environmental imperatives did not remain mutually exclusive, and that both can be taken care of, even while striving to meet the aspirations of India’s 1.3 billion plus population.

The First Step: Managing the Coal Quagmire

In 2014, when Modi Government came to power, among many other issues, it had to deal with a major coal supply crisis that India’s thermal based power sector was perpetually grappling with. It was indeed an irony that while India, by 2014, had more than 300 billion tonnes of geological resource of coal that was good enough to take care of India’s requirements for more than 200 years, the country nevertheless continued to suffer from supply side problem of coal.

The crisis that had gathered pace for years was so profound that on most occasions, India was not even producing more than 160 gigawatts of electricity even when its installed capacity had touched the 250 gigawatts mark in 2014.

A FICCI report had quantified the economic loss, as a result of this power deficit, at $64 billion for 2011/12 . Most major thermal power plants had a precarious reserve of barely a few days of coal stock. A major part, if not the only part, of the problem was the sheer inability of Coal India to raise the quantum of annual mining of coal.

If the coal supply shortage crisis was not enough, the coal allocation scam, commonly called ‘Coalgate’, that allegedly happened during UPA era, did the rest in terms of making sure that the coal supply shortage crisis remained as it was.

Coal Swapping: A Simple Step to Solve a Gigantic Problem

For Modi Government, the coal supply problem was manifold but a start had to be made somewhere in terms of plugging the gaps. One of the first steps in that direction was approval that was given by Union Power Ministry for swapping the coal supply sources of power utilities run by Gujarat Government and NTPC. This was a major step towards rationalising the coal sourcing matrix of power utilities in the country, which was aimed at making sure that thermal power plants were allowed to source coal from the mines nearest to it. This had a manifold impact in terms of reducing the cost of transport, time taken for transport, and the eventual stock maintenance dynamics of thermal power plants.

While this was a simple solution to save time and cost for thermal power plants, the irony was that for long, power utilities of western India were allocated coal from mines in eastern India, while the plants in eastern India were getting coal linkages from coal mines in west and central part of India. And yet, no one before Modi Government had envisaged the idea of rationalising the coal linkages to reduce time, cost and overall power supply situation.

The particular swap in contention, namely the NTPC-Gujarat swap had a peculiar scenario wherein NTPC’s power plants in Chhattisgarh were being fed by coal that was being imported and landed at ports in Gujarat, while the power plants run by Gujarat Government were fed from coal mined from the Korea Rewa mines in South Eastern Coalfields. A simple rejig by Modi Government made it possible to save money to the tune of Rs 400-500 crore.

In early 2015, a full-fledged coal swapping scheme was given approval by Government of India that initially included 19 power plants of state-run utilities like NTPC, DVC and a few states. Later, this scheme and its benefits were extended to private sector utilities and non-regulated sector as well. This indeed had a remarkable impact in terms of cost of power generation coming down due to supply chain efficiency.

Harnessing the SHAKTI Policy

The coal swapping policy was followed by another landmark policy initiative of coal linkage namely ‘Scheme for Harnessing and Allocating Koyala (Coal) Transparently in India’ or SHAKTI.

The SHAKTI scheme in principle made sure that coal linkage facility for IPPs or the Independent Power Producers, became far more transparent, cost effective and convenient than what it used to be previously. The SHAKTI scheme had provision for coal linkage for both types of IPPs, one which has long term Power Purchase Agreement or PPA with state utilities, and the ones which did not yet have the same.

The coal linkage policy made sure that dependence of IPPs on expensive imported coal comes down, and drastically put to an end the previous ad hoc policy of discretionary allocation of coal. It also gave a fresh lease of life to considerable amount of stranded assets in the power sector which for lack of coal linkage was not in a position to become operational. The SHAKTI scheme therefore came as a relief for the banks as well, since a considerable amount of stranded assets in the power sector was now getting operational as a result of the SHAKTI scheme. Stranded assets result in rise in NPA or Non Performing Assets of banks. Operationalisation of stranded power plants was thus a big relief for those banks who had lent money for such projects

Auctioning of Coal: Bold, Transparent and Efficient

The third, and perhaps one of the most critical aspects of India’s coal policy during the Modi era has been the coal block auction process that was started in June 2020, and made sure that some of the idiosyncrasies of the coal sector of India, were addressed.

India’s rapid pace of development necessitated need for huge amount of electricity generation. The peculiarity of the Indian context was that India in spite of having one of the largest repositories of coal reserves in the world, was perpetually dependent on imports, so much so that it got the dubious distinction of being the second largest importer of coal in the world. While India was importing almost around 235 million tonnes of coal (2019), at a humongous cost of around Rs 1.71 lakh crore, interestingly, as per reports, almost around 135 million tonnes of additional coal could be additionally sourced from domestic sources, if India could enhance its annual production of coal. This is precisely what the auction-based initiation of commercial mining was aimed at, since having a robust mining policy is the bedrock for any country’s journey towards self-sufficiency and economic progress.

It was not that suddenly, as a result of the initiation of the auction process, India’s coal import would come down. But as a step, it was one in the right direction, which over a period of time is expected to considerably reduce India’s dependence on coal import, even as India’s quantum of coal requirement would continue to rise.

The anomaly of India’s underutilisation of its coal mining capacity was needed to be addressed in a transparent and pragmatic manner after the coal block allocation for captive mining by the previous regime was quashed by judiciary. After necessary amendments were made in the Mines & Mineral (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957 and the Coal Mines (Special Provisions) Act, 2015, the Mineral Laws (Amendment) Act, 2020 became the basis for auctions for commercial mining.

The auctioneering process paved the way for intense competition among bidders and eventually this process was far more transparent and competitive than the method that was applied by the previous regime for coal block allocation. Eventually, liberalisation of India’s coal mining sector was necessary just like it has been for several other sectors, for enhancing productivity, introduction of better technology, increasing revenue for the exchequer, and reducing dependence on the state-run monopolies in the sector. It also replaced the culture of multiple licenses by a policy of issuing single composite license, namely prospective license-cum mining lease.

The new policy also did away with the sectoral restrictions on usage of coal and gave freedom to coal miners to either use it for captive purpose, or sale to others. As per reports, India has so far auctioned and allocated 133 mines that have a combined capacity at peak level to the tune of 540 million tons per annum.

The above-mentioned policy initiatives could be summarised as creation of the regulatory policy framework that was comparable to the global benchmarks, and which was hitherto lacking in coal sector. Given the complexities associated with India’s energy market, these were definitely stepping stones in right direction. However, the work was far from over.

Enhancing the Productivity of Coal India

Apart from the policy initiatives for the coal sector, one key area of focus, and the most critical one, was to enhance the productivity of Coal India Ltd.

| A Press Information Bureau press release of 3rd May, 2023 states the following

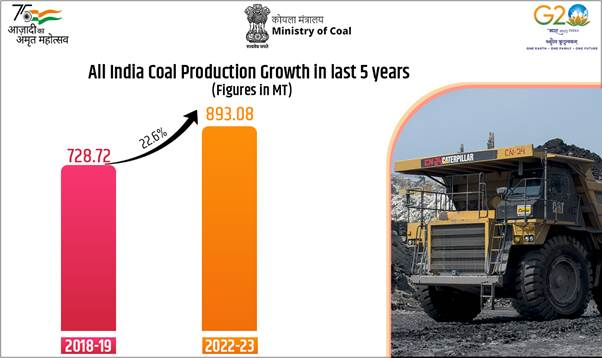

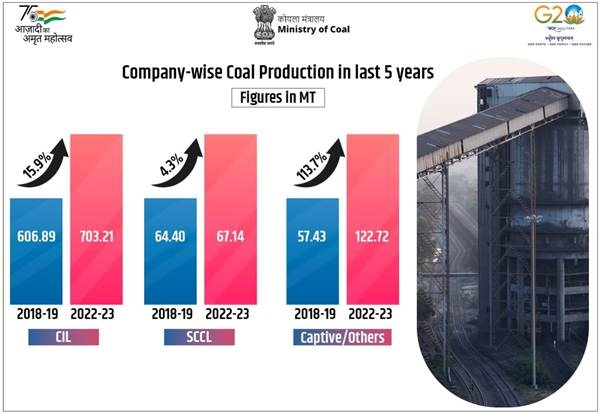

India’s overall coal Production has seen a quantum jump to 893.08 MT in FY 2022- 23 as compared to 728.72 MT in FY 2018-2019 with a growth of about 22.6%. The priority of the Ministry is to enhance the domestic coal production to reduce the dependence on substitutable coal imports. In the last 5 years, the production of Coal India Limited (CIL) has increased by 703.21 MT (Million tonnes) as compared to 606.89 MT in FY 2018-2019 with a growth of 15.9%. SCCL has shown impressive growth at 67.14 MT in FY 2022-23 from 64.40 MT in FY 2018-19 with a growth of 4.3%. Captive and other mines have also taken a lead in coal production by 122.72 MT in FY 2022-23 from 57.43 MT in FY 2018-19 with a growth of 113.7%. Ministry of Coal has initiated several measures to ramp up the domestic coal production to achieve self-reliance to meet the demand of all sectors and ensure adequate coal stocks at thermal Power Plants. The exceptional growth in coal production has paved the way for energy security of the Nation. The annual Coal Production target set for the FY 2023- 2024 is 1012 MT. Source- Press Information Bureau |

Source- Press Information Bureau

It is evident from the graphs that the efficiency of Coal India has indeed been enhanced in the last few years. The aim for the near and immediate future is to have a capacity to mine a billion ton of coal annually. Hopefully, a combination of an improved Coal India Ltd and expansion of private coal mining would eventually solve India’s coal conundrum in the coming decade, when India’s demand for energy would be at its peak to fuel an economy racing towards the $10 trillion mark by 2035.

Why it was a Big Deal to Reform the Coal Sector

One has to remember that even as India under PM Modi’s leadership has made giant strides in the realm of renewable energy development as well, with India now having one of the largest installed capacities of renewable energy generation in the world, it was imperative for India not to give up on its coal usage since comprehensive transition to renewable energy development would take time and commensurate investments.

Also, from the standpoint of grid stability, thermal continues to be more stable than rest, and there was no reason for India to abandon usage coal because of pressure of western lobbies since the west has no legitimate authority to pontificate on environment, given what it has done for centuries in terms of degrading the same. While India remains conscious of its environmental responsibilities given its traditional and cultural ethos of conservation of nature, India’s shift from coal to renewable has to be calibrated and gradual, so that it does not impact India’s growth imperatives, considering that the country has to provide for the needs and aspirations of 1.4 billion people.

The irony however was that it was not the west but India’s own policy paralysis of the past that impeded its optimal utilisation of its coal resources. It is from this perspective that the initiatives taken by Modi Government in the last nine years, in terms of ushering in structural reforms in the coal mining sector, can in certain ways be termed as a game changer.

While not much is discussed in mainstream media on the path-breaking reforms made in coal sector in the last nine years, and their resultant positive impacts, one simply cannot deny that the reforms initiated in the same are no less significant from the standpoint of setting the course to make India ready to fuel its quest to become a $10 trillion economy in the coming one decade. Credit for the same invariably goes to PM Modi led NDA Government, more so because it not only cleaned up the mess left behind in the sector by the previous regime, but also laid the foundation to unleash the true potential of India’s coal mining sector through bold and visionary reforms.

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)