Jogendra Nath Mandal’s 115th birth anniversary passed on January 29. It is interesting to observe that Mandal’s legacy has made a comeback to a certain extent, at least, among a section. The communists and the self-proclaimed Dalit leaders, whose principal protest points these days are the steps of the Jama Masjid and Shaheen Bagh in the national capital avoid speaking of or referring to Mandal. His life is difficult for them to explain because he exposes their stand and false argument against CAA.

Mandal, himself, a Dalit Hindu, member of the Muslim League, the first Law Minister of Pakistan, was forced to flee within three years after Pakistan was formed. He had clearly come to the conclusion, “after an anxious and prolonged struggle”, as he stated in his historic resignation letter from the Pakistan cabinet on October 9, 1950, that “Pakistan is no place for Hindus to live in and that their future is darkened by the ominous shadow of conversion or liquidation. The bulk of the upper-class Hindus and politically conscious scheduled castes have left East Bengal. Those Hindus who will continue to stay accursed in Pakistan will, I am afraid, by gradual stages and in a planned manner be either converted to Islam or completely exterminated…”

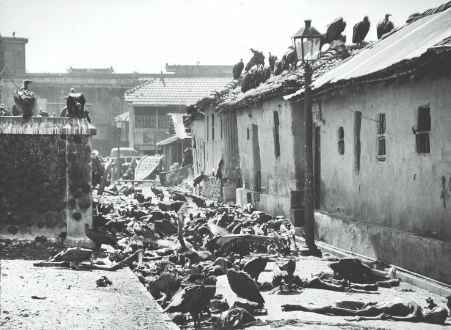

Over the decades to come, that is exactly what happened to the Hindus and other minorities in Pakistan. Communists were driven out or exterminated and Dalit Hindus too were tortured and driven out in large numbers. Strange then, that a group of self-arrogating Dalit ‘leaders’ and communists are loudest in their opposition to granting citizenship to refugees, the bulk of whom are Dalits. I have written about this in my past columns but it is a point that needs to be reiterated. Especially during 1971, Bangladesh liberation war, the Bengali Dalit Hindu refugees bore the brunt of the Pakistan army’s genocide, a genocide for which it has never been tried, a demand for a trial was never made by the European Union and human rights activists based in the West.

In fact, as figures, point out, until June 1971, by when the Pakistan army had unleashed a reign of terror in East Pakistan, especially targeting Bengali Hindus, 5.5 million refugees had come into India, out of which 90 per cent were Bengali Hindus. Among these were small shop keepers, small tillers, fishermen, boatmen, vegetable vendors and washer-men, whose villages were pillaged, whose womenfolk were targeted, whose market and ghat was gutted by the Pakistani army marauders and their collaborators, the Ansars and the Razakars, armed fronts of Islamist organisations. The present incarnations of these elements in India are fronts such as the PFI and the SDPI, whose sole agenda is the establishment of a Caliphate in India. PFI cadres, in a recent anti-CAA protest march in Kerala, vowed to usher in the Caliphate and reminded those who support CAA, of the Moplah riots of 1921, in which Islamists had massacred a large number of Hindus. Of the Moplah riots, Dr Ambedkar wrote, in his provocative, “Pakistan or the Partition of India” that “what baffled most was the treatment accorded by the Moplahs to the Hindus of Malabar. The Hindus were visited by a dire fate at the hands of the Moplahs. Massacres, forcible conversions, desecration of temples, foul outrages upon women… all the accompaniments of brutal and unrestrained barbarism, were perpetrated freely by the Moplahs upon the Hindus…” One has not heard a word of condemnation against such a blatantly revanchist stand by the PFI ‘brown-shirts’ from those who profess to base their politics on Dr Ambedkar’s legacy!

As I have argued, communists who are the loudest in their protest against CAA, forget that their ideological compatriots in Pakistan were not spared either. Ayub, for instance, saw Hindus and communists as equal threats to Pakistan. In her well-argued and minutely documented work, “Purifying the Land of the Pure: Pakistan’s Religious Minorities”, Pakistani journalist and former member of the Pakistan National Assembly, Farahnaz Ispahani, for example, observed how “Ayub saw Hinduism and communism as equal threats to Pakistan.” In 1959, in a foreword to a book, “The Ideology of Pakistan and its Implementation”, Ayub wrote, that “one of the questions of concern for Pakistanis was how can the offensive of Hinduism and Communism against the ideology of Islam be combated?”

By thus opposing CAA, the reason, historically, for enacting and amending of the Islamic character of Pakistan and its insistence that minorities must live there as an inferior and captive population, Indian communists are displaying a shameless disregard for the past. By expressing solidarity with Shaheen Bagh where repeated demands have been made for dismembering India, for implementing Sharia and for ensuring that all talk of equality is mere prattle till Islamic rule is established in India, Comrade Sitaram Yechuri has clearly indicated, that Indian communists, for a second time since supporting Jinnah’s Pakistan resolution, have again thrown in their lot with Islamists who wish to usher in the rule of Sharia and reject the Indian Constitution.

In a way, the protest against the CAA is to be welcomed; it has exposed and clarified the stand and positions of a number of political parties. The Congress, for instance, has extended its unequivocal support for the PFI. With the Kapil Sibal expose, it has now been clearly established that Rahul and Sonia Gandhi’s Congress has forged a “vibrant” partnership with the break-India fringe element.

But let us return to Jogendra Nath’s Mandal’s lament, which remains the anti-thesis to the theory of a Dalit-Islamist alliance. In a confidential conversation in Dhaka, with the representative of a leading Indian English daily, months before his eventual resignation, Mandal described the increasingly deteriorating conditions of minorities. He described a “large number of instances where officialdom and Muslims alike were making life hell for Hindus. Open threats are being issued to Hindus to marry their womenfolk to Muslims. Money is being extorted in the guise of giving protection to them from hooligans. If Hindus dare report to the authorities, punishment often descends upon them. Houses and crops are destroyed and women molested. Koranic prayers are to be said in every school and every Hindu is to attend standing…Hindu names of schools are being changed to Muslim names. Without contributing a pie to the funds of the schools, Muslims are being given 50 per cent or more representation in the administrative bodies. In district and union board elections under joint electorates, Hindus are being terrorised not to vote so as to get as many Muslims elected as possible…”

In January 1950, it became evident that Pakistan’s trajectory as an Islamic state was beginning to have a visible effect on its minorities when a large scale pogrom was unleashed on Hindus in East Bengal. It was the start of a cycle of violence that would keep recurring at regular intervals over the decades. Referring to that phase, the Indian Commission of Jurists (ICJ) for example, in a report in 1965, titled, “Recurrent Exodus of Minorities from East Pakistan and Disturbances in India: a Report to the Indian Commission of Jurists by its Committee of Enquiry”, observed how, after the violence, “A large scale requisitioning of Hindu houses and properties took place. The educational institutions were largely manned by Hindus and practically all the schools were run by Hindus. There was a squeeze of the teachers and professors in order to make room for Muslims. Hindu students were forced to leave the hostels. Thus, attempts were made to dislodge the Hindus from their dominant position. This discrimination, unfortunately, went right down the scale to the petty shopkeeper and the small landholder. The result was that even those who had stayed behind with the intention of making East Pakistan their home, because they were born and brought up in that area, began to feel that life would be very difficult for them and the migration continued…”

The situation in 1965, when this particular exhaustive report was drafted by the likes of Purushottam Trikamdas and others, was no different, the only difference being that the minorities in Pakistan, especially East Pakistan had seen huge depletion by then. Mandal’s prediction of “extermination” by “gradual stages” was proved right.

The real tribute, thus, to Jogendra Nath Mandal would be to recollect him, to remember and disseminate his predictions and lament, to contextualise him in the present CAA narrative, to give him his due for having exposed Pakistan in the early years, for having spoken up for the persecuted Dalit Hindus. His legacy has been deliberately suppressed for too long, it needs to be reinstated.

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)