For many of our generation, then in college, Vajpayee becoming Prime Minister was the response that we had yearned for to Congress’s politics of status quoism and entitlement. It was the first triumph, at the national level, of the politics of an alternate vision

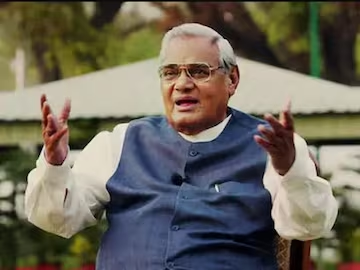

The commemoration of Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s centenary will take off in an India that he had always dreamt of and aspired for. It is an India that countless political workers, whom he led, had imagined and struggled for.

The commitment to India first, the realisation of one nation, one Constitution through the abrogation of Article 370, an enhanced and visible focus on a successful strategisation of national security, the pragmatic and successful exercising of foreign policy options to realise both our strategic and civilisational goals, the undiluted focus on development and cultural inheritance, the emphasis on further deepening the foundations of world-class infrastructure as well as a comprehensive and intense reaching out to the marginalised by making basics available to them and by an emphasis on their self-dependence, the ideation and articulation of a comprehensive and refreshing educational vision and roadmap, the enunciation of an active and confident schema for realising and actualising the spirit of self-reliance, and above all an undeterred, undiminished and fundamental commitment to India’s democratic and constitutional essence and fabric are all tributes to the legacy of Atal Bihari Vajpayee or “Atal ji”, as he was endearingly referred to by the teeming millions of all rank and file.

On a personal note, belonging to a generation that had grown up seeing Atal ji’s visuals and listening to his oratory and which had come of age when he took oath as the first BJP Prime Minister, after decades of relentless and dogged struggle, I vividly recall the ebullient thrill, the electrifying sensation of seeing him take oath for the first time, and the crestfallen devastation of seeing him having to resign just after thirteen days. That same thrill returned more intensely when we saw him bounce back and take oath again after a phase of uncertainty and confusion.

It was a lingering regret, for many of our age who graduated to the wide world in 1997, that he did not address the nation as Prime Minister on the 50th year of its independence, and one had to settle for an assortment that had then passed off as a government. That omission was amply made up during the 75th year of freedom by a Prime Minister who, in many ways, can be termed as Vajpayee’s political, governance, and intellectual heir. He amplified, magnified, and added to his legacy in manifold ways through a vision that was seeded, in many ways, by Vajpayee in his years of struggle and power.

Manasputra, “born of mind”, is an exalted description in our epics and scriptures, an apt portrayal of an heir, a successor who not only carries forward a noble legacy but raises it to unprecedented levels of achievements and of realisation, surpassing the original and leaving a deep and indelible imprint on an age and an era. Narendra Modi, as Prime Minister, fits into that description—unarguably Vajpayee’s Manasputra, magnifying his legacy and shaping an era, creating an epoch that will drive India for the next quarter century and beyond.

For many of our generation, then in college, Vajpayee becoming Prime Minister was the response that we had yearned for to Congress’s politics of status quoism and entitlement. It was the first triumph at the national level of the politics of an alternate vision. It showed that a non-Congress leader and dispensation could finally arrive on its own and stand out. The Jana Sangh earlier and the BJP later proved with Vajpayee’s ascendancy as Prime Minister that five decades in opposition was a phase of relentless preparation leading to the actualisation of the dream and vision of a political ideal.

For most parties, which have had to spend seemingly interminable phases in opposition, existence itself becomes a challenge. Many have withered or have disintegrated after spells in opposition. That was not an option for Vajpayee and his comrade-in-arms LK Advani and the legions of leaders and workers they led and nurtured. Twice bereft of a towering leadership and guide, once in 1953 with Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee’s sudden death and the second time, at a crucial phase in 1968, with Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya’s death, the political movement the former seeded and the latter nurtured and led for a long spell, survived evolving through challenging vicissitudes, as India’s ruling party.

Vajpayee’s reminiscences aptly describe that challenging early phase. During the second general elections in 1957, when Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee’s protective presence was absent, Vajpayee wrote: “My party, Bharatiya Jana Sangh, was engaged in a gigantic task of establishing itself. The benign presence of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee was no longer there. Neither was there a distinguished leadership nor was there a wide mass base. Candidates were hard to find to fight the elections. There was none who was willing to spend his own money to face forfeiture of security deposit. Even so, elections had to be fought. What better chance could there be to spread the message of the Party to the vast masses to the maximum extent possible?’ There was no looking back, no stopping, from there onwards.”

Source:

https://www.news18.com/opinion/opinion-atal-bihari-vajpayee-a-centennial-reflection-9168004.html

Author

-

(The writer is a Member, National Executive Committee (NEC), BJP and Chairman of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal)

View all posts

(The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organisation)